Webinar

February 26

Better SOC with Interactive Sandbox

Practical Use Cases

A rootkit is a type of malicious software designed to provide unauthorized administrative-level access to a computer or network while concealing its presence. Rootkits are tools used by cybercriminals to hide their activities, including keyloggers, spyware, and other malware, often enabling long-term system exploitation.

757

757

0

0

467

467

0

0

2699

2699

0

0

A rootkit is a type of malicious software designed to gain unauthorized administrative access to a computer system, usually hiding its presence by subverting standard operating system processes or tools, making detection and removal difficult.

Rootkits operate at a low level (kernel or firmware) within a system’s architecture, granting attackers privileged access while employing advanced obfuscation techniques to evade antivirus software and system monitoring utilities.

Reaching the endpoint, rootkits typically alter system files — modify binaries, drivers, or firmware to remain hidden. They survive reboots, avoid detection by standard antivirus software, and intercept system calls which often includes manipulating APIs to mask their activities and the presence of associated malware.

Rootkit mechanics depend on their type:

Mechanics often involve “hooking” (intercepting function calls), patching (altering system code), or injecting malicious code into memory. For example, a kernel-level rootkit might use Direct Kernel Object Manipulation (DKOM) to hide processes by altering kernel data structures directly.

Rootkits ground themselves deep within a system, often at the kernel level (in the core of the operating system) or even lower, like in firmware or hardware. They get there by exploiting vulnerabilities, leveraging social engineering (e.g., tricking a user into installing something), or piggybacking on seemingly legitimate software. Once installed, they modify the OS or other critical components to hide their existence and activities. This can involve:

A typical rootkit attack follows these stages:

Infection. The rootkit enters, often through a phishing email, malicious download, or by exploiting a software vulnerability (e.g., a zero-day exploit).

Privilege Escalation. The malware lifts its permissions to root/admin level, either by exploiting flaws in the OS or stealing credentials.

Installation. The rootkit embeds itself in a critical area (e.g., kernel, boot sector) and modifies system components to hide itself.

Execution. It performs its key task — data theft, espionage, creating backdoors — while remaining undetected.

Persistence and Evasion. It ensures it survives reboots and evades detection by antivirus or system monitoring tools.

The attack might go unnoticed for months or years, as rootkits are designed for stealth. You might only notice something’s off if the system slows down, behaves oddly (e.g., unexplained network traffic), or if a security tool catches a secondary infection tied to the rootkit.

Most importantly, rootkits provide backdoor access allowing criminals to remotely control the system. They modify system behavior: inject malicious code and manipulate system processes. Rootkits hide their activities, conceal files, processes, and network connections. These programs steal valuable information: capture passwords, login credentials, payment data, keystrokes, and personal data. They can activate microphones, cameras, or network sniffing to spy on the user.

Some rootkits corrupt files, disable security software, or brick the system entirely (e.g., by overwriting firmware). Many of the kind turn the infected machine into a bot, using it for DDoS attacks or crypto mining without the user’s knowledge.

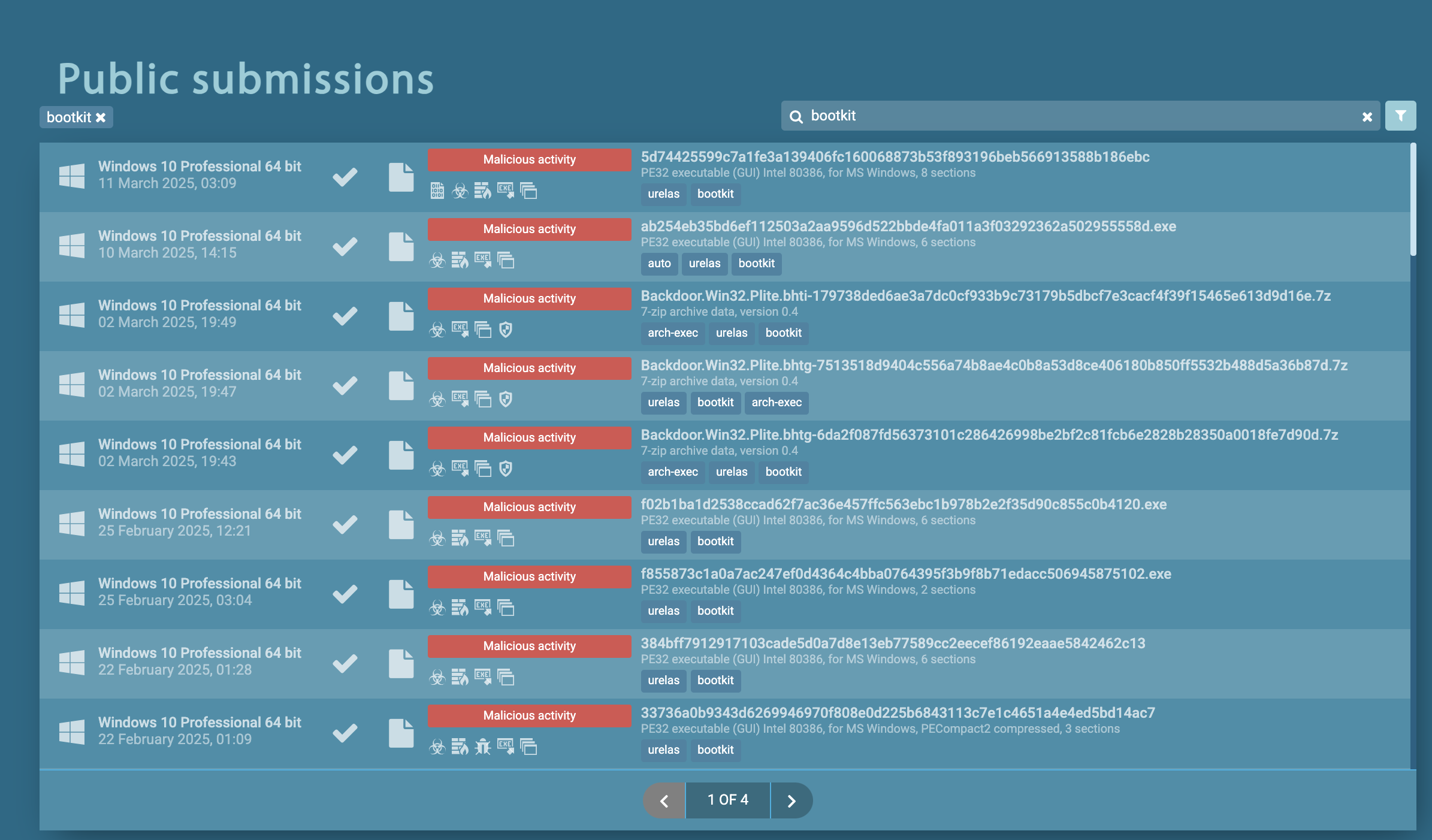

Let’s research a rootkit’s operations on the example of Urelas bootkit. There are a number of freshly added samples of this malware in ANY.RUN’s interactive sandbox.

New samples of Urelas bootkit in public reports

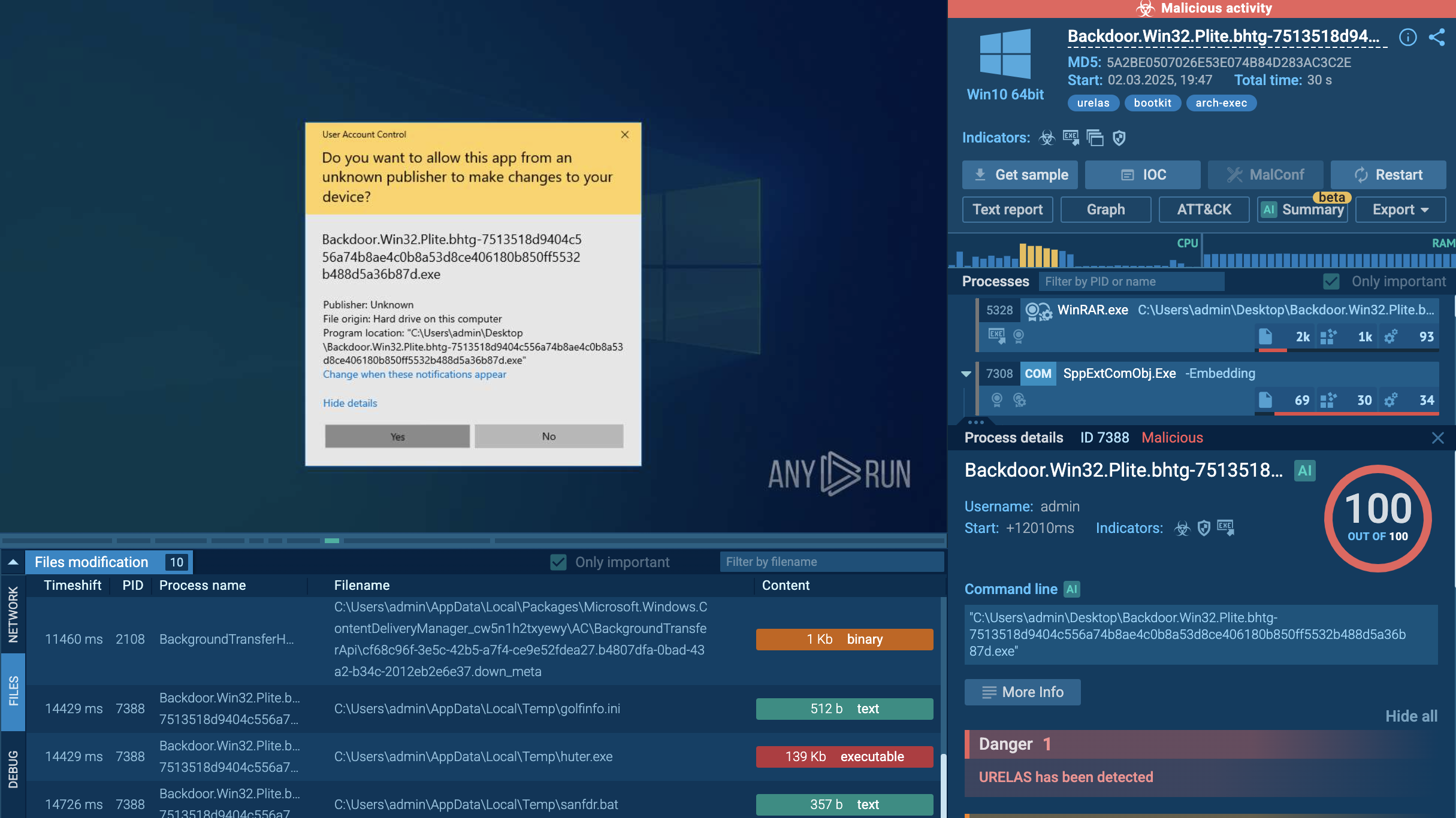

Upon execution, the dropper may perform various checks to confirm it is running in a suitable environment, such as verifying the operating system version or detecting the presence of security software. If these conditions are met, the dropper proceeds to load the rootkit.

Urelas bootkit in action in ANY.RUN's Interactive Sandbox

Once installed, Urelas employs advanced stealth mechanisms to hide its presence from both users and security tools. It hooks into critical system calls using various techniques to obscure its files and processes, preventing them from appearing in standard system monitoring tools. The rootkit's functionality also includes privilege escalation capabilities, enabling it to gain higher-level access within the compromised system.

Communication with command-and-control (C2) servers is another critical aspect of Urelas's operation. After installation, the rootkit establishes a secure connection to its C2 infrastructure, allowing attackers to issue commands remotely. This communication can include instructions for data exfiltration, further exploitation of the compromised system, or even lateral movement within a network.

To maintain persistence, Urelas may modify system configurations and create new entries in startup processes. This ensures that even if the system is rebooted or if attempts are made to remove it, the rootkit can quickly re-establish itself.

ANY.RUN's Interactive Sandbox allows to detonate rootkits on virtual machine with set-up parameters study their interaction with an attacked system in detail.

Rootkits are quite destructive, but maintaining the basic digital hygiene can help minimise the risk. Keep your systems updated, regularly patch OSs, software, and firmware. Avoid downloading apps from unverified sources and check digital signatures.

Protect the boot process from tampering by allowing only trusted software to load. Use security software that includes rootkit detection and employs behavior analysis. Specifically, rootkit scanning tools like GMER, Malwarebytes Anti-Rootkit, and Microsoft's RootkitRevealer.

To minimize the risk of rootkit attacks, organizations should take a proactive approach to cybersecurity, implement robust safety policies, and keep their detection systems up to date. Malicious and suspicious files and links must be analyzed in a sandbox, and tools like Threat Intelligence Lookup must be employed to monitor actual and emerging threats.

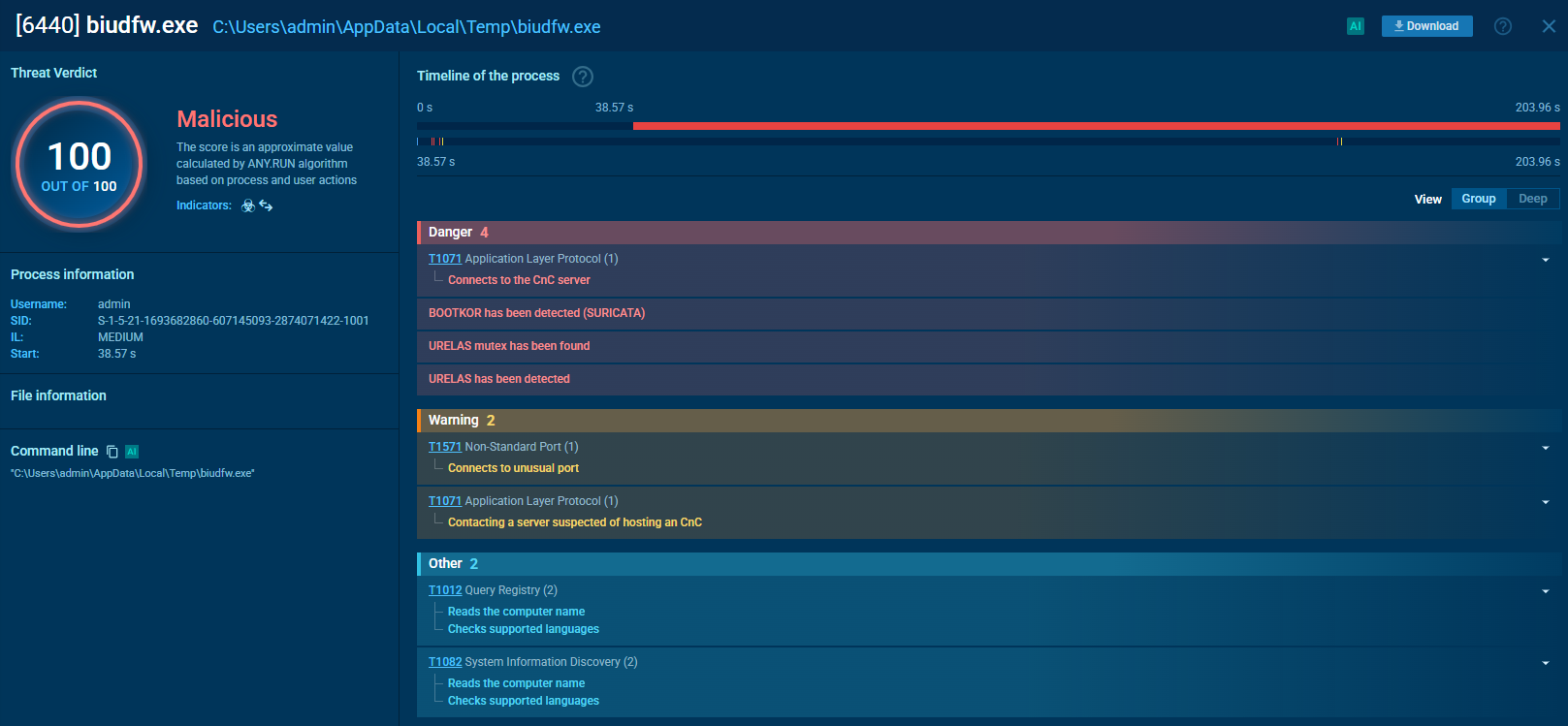

Rootkits can be detected by a number of indicators of compromise. In this example, a malicious process of a bootkit triggered a Suricata rule and presented itself via an associated mutex:

A rootkit process detected by Suricata and mutexes in ANY.RUN TI Lookup

Rootkits are nasty as they’re designed to evade detection and traditional defenses. But staying proactive with updates, security tools, and safe habits can keep most of them at bay. Use ANY.RUN’s interactive sandbox to check suspicious files and links and study the behavior of rootkits; leverage Threat Intelligence Lookup to gather indicators for detection and response.

Get 50 requests in TI Lookup to collect IOCs on persistent and new rootkits and prevent major damage