Recently, we’ve discovered an interesting LaplasClipper sample here at ANY.RUN, and we’re going to analyze it in this article. Our LaplasClipper sample is written in .NET and obfuscated with Bable.

We will dig into the sample’s configuration, study, and ultimately break through the primary obfuscation techniques the attackers employed to make the analysis process more difficult.

What is LaplasClipper malware?

LaplasClipper, as its name implies, is a clipper variant. Its primary malicious function is to monitor the user’s clipboard (T1115). Attackers typically use it to swap out cryptocurrency addresses with ones they control. When users paste the address into a wallet to transfer funds, it’s the attacker’s address that receives them.

Taking the First Step of our LaplasClipper Analysis: Reconnaissance

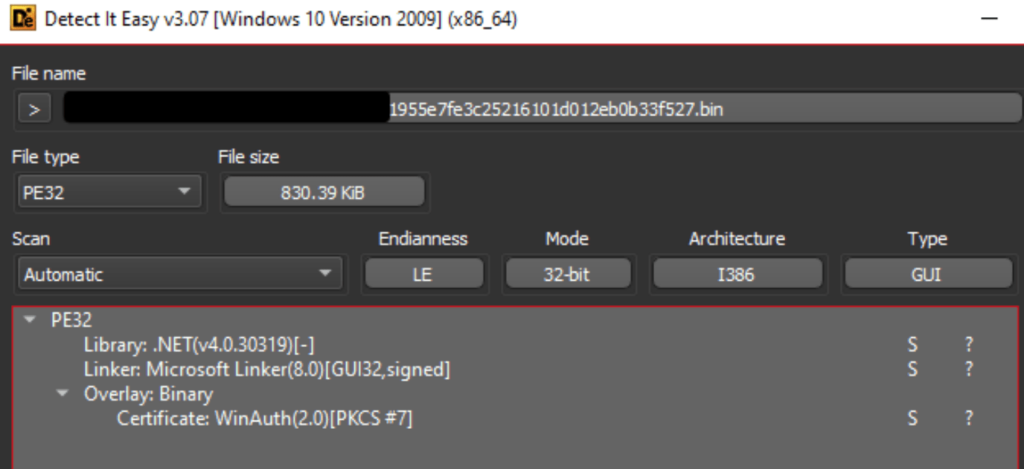

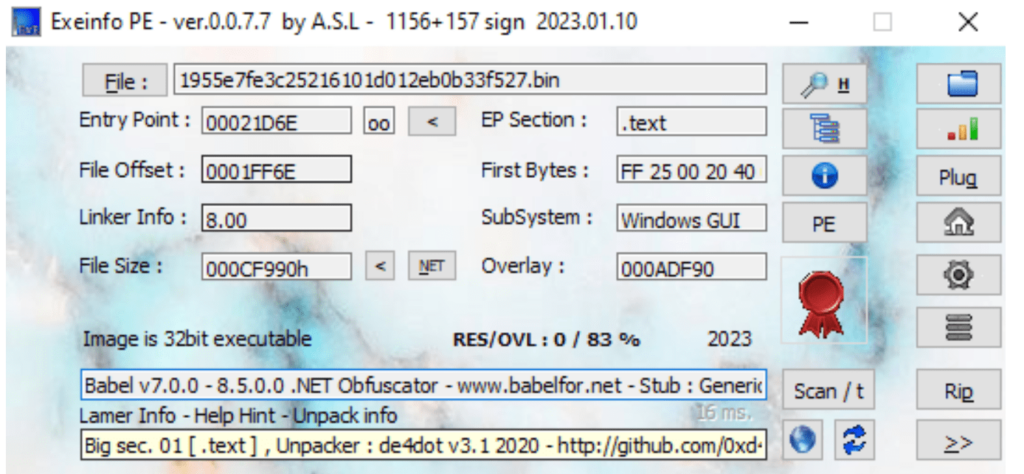

For today’s analysis, we’re going to dissect this Laplas sample. To understand what we’re dealing with, we’re immediately going to feed it into two tools: DIE and ExeinfoPE.

Right away, we see that it’s .NET obfuscated by Babel (T1027.002). And we also get a link to an unpacker in the form of de4dot. We’ll use this clue later.

The Babel Obfuscator is one of the most popular proprietary obfuscators for .NET. It has the following set of features:

- Renaming symbols

- Encryption of strings and constants

- Packing and encrypting resources

- Virtualization and obfuscation of the code

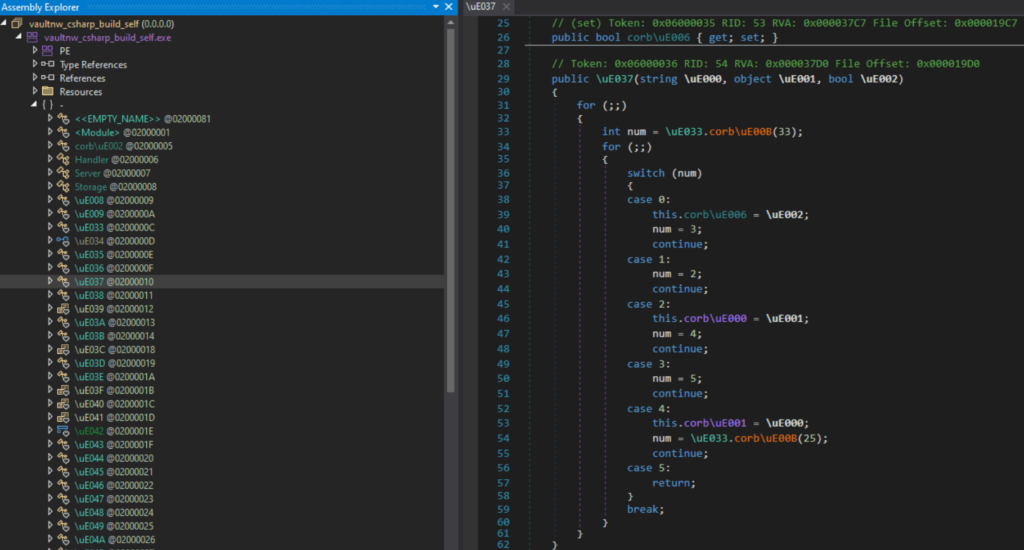

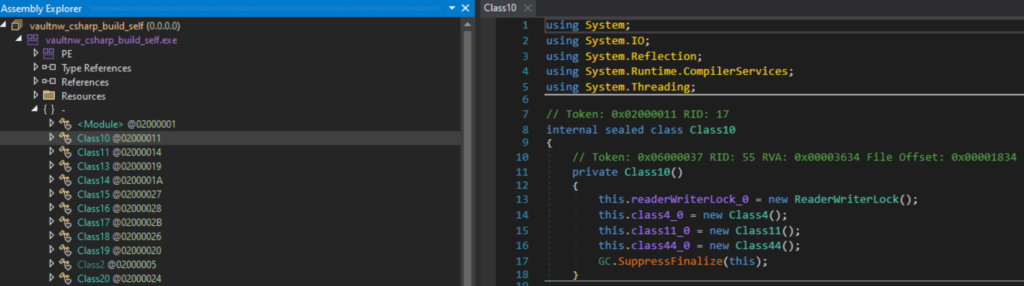

Let’s upload our sample into dnSpy to study it further. Here’s what we see:

Immediately noticeable are the distorted objects’ names, and in the code, we can see the obfuscation of control flow using the switch conditional statement. To improve code readability and simplify our further analysis, let’s pass our sample through de4dot and BabelDeobfuscator.

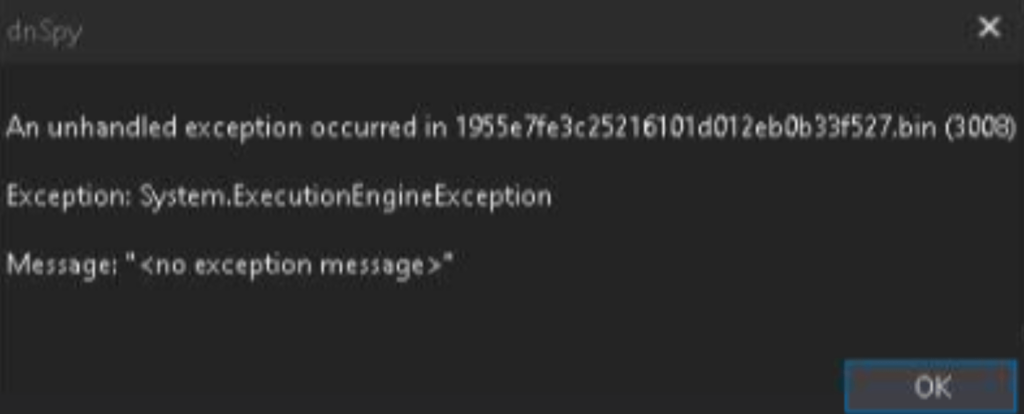

Now the situation has improved a bit, but the cleaned version is only suitable for static analysis. However, if we try to debug the original sample, it will fail and throw an error of the following type (debugging is recommended to be performed only in an isolated environment):

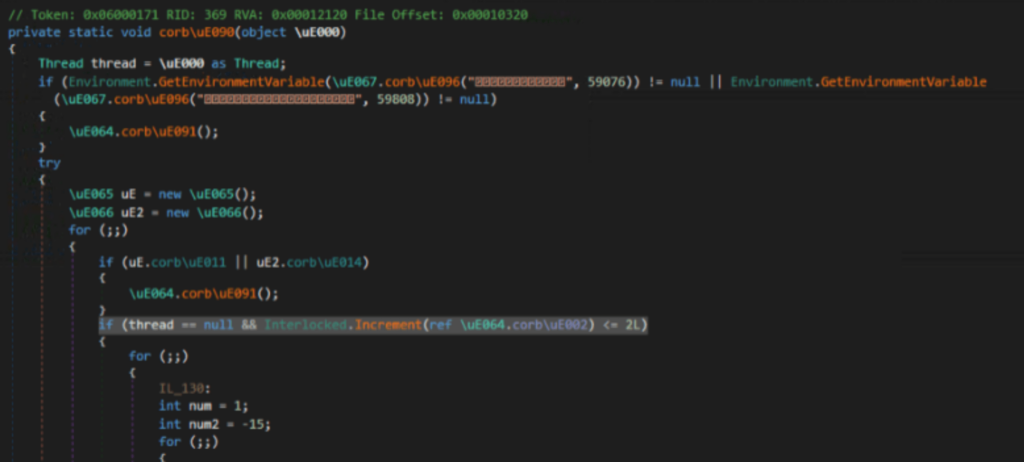

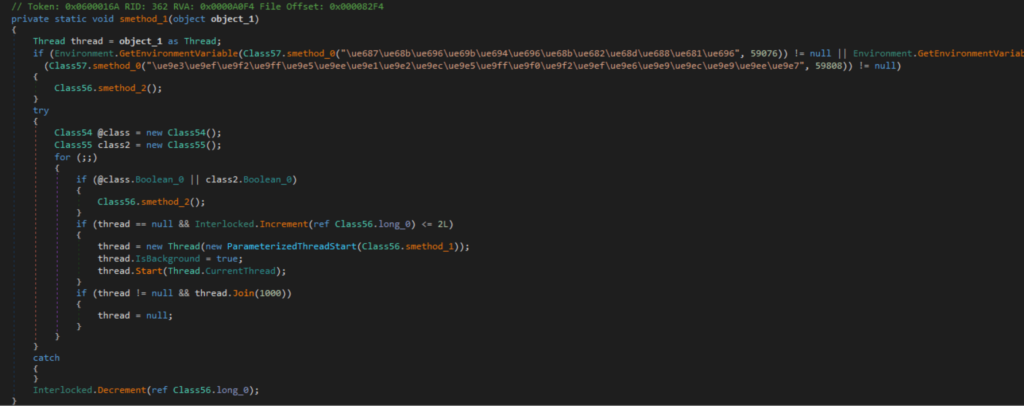

If we look at the top of the call stack, we’ll see that the program crashes in some kind of environment variables check statement:

Let’s find this method by references to the use of GetEnvironmentVariable (T1082) in our cleaned sample.

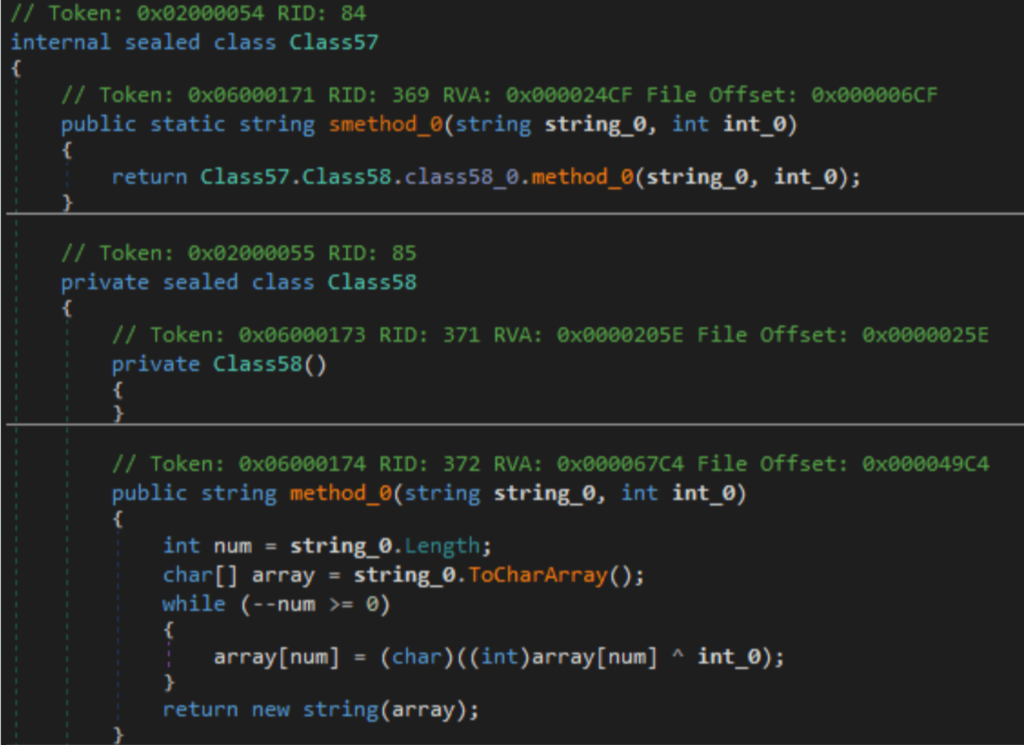

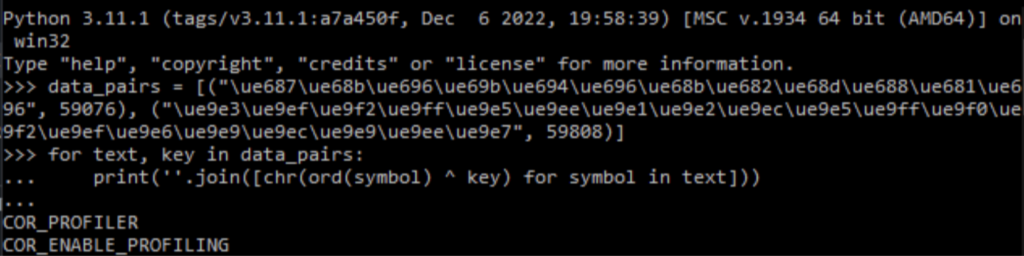

The strings are decrypted dynamically, using a trivial XOR. The key is specified as the second parameter on the method.

Let’s use a Python interpreter (you could also use CyberChef or simply set a break point) to see which environment variables are being checked.

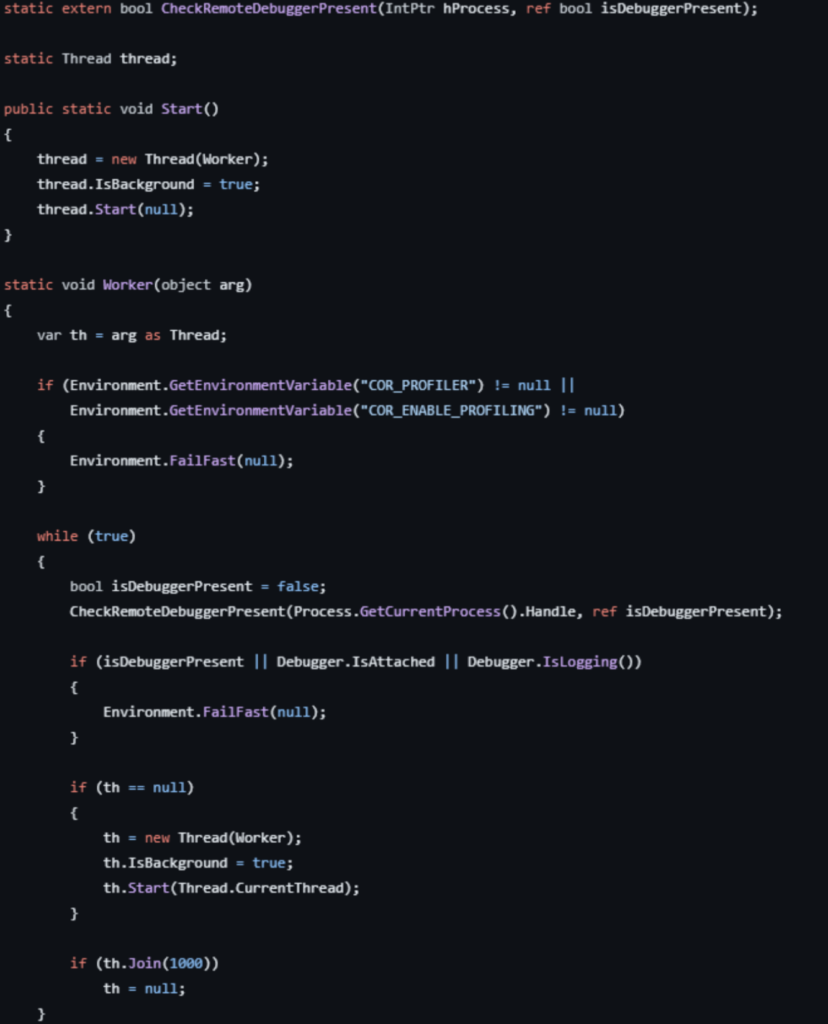

After a brief search using keywords in combination with environment variables, we found the code for this anti-debug method (T1622), and it turns out it was written by the obfuscator developers themselves.

The method turned out to be rather ordinary. To bypass his anti-debug trick, we can simply halt the second thread during the debugging process, without the need to modify the sample. We just need to set a breakpoint at the beginning of the routine.

So far, we’ve conducted basic reconnaissance and determined methods for partially disarming the target. However, if we try to decrypt the remaining strings in the same way as before, we won’t find any hint of C2 or other evidence of illicit activity, apart from the Babel debug strings and function names intended for dynamic invocation.

Digging deeper into our LaplasClipper sample

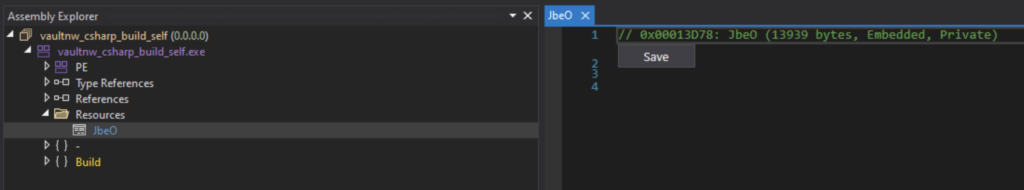

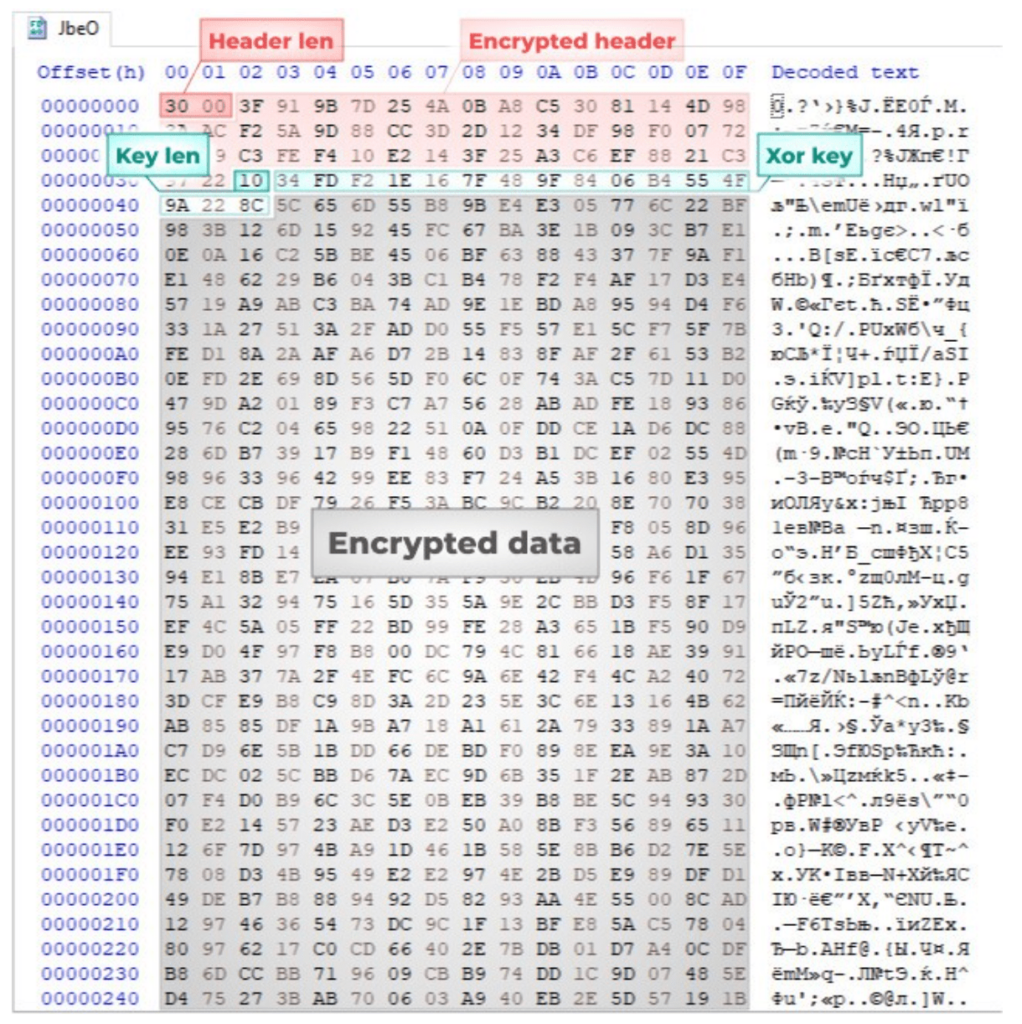

If we take a closer look at the sample, we’ll notice a resource named “JbeO” — note its rather substantial size.

Let’s make an assumption. If this resource is present, it’s likely that it’s used for something.

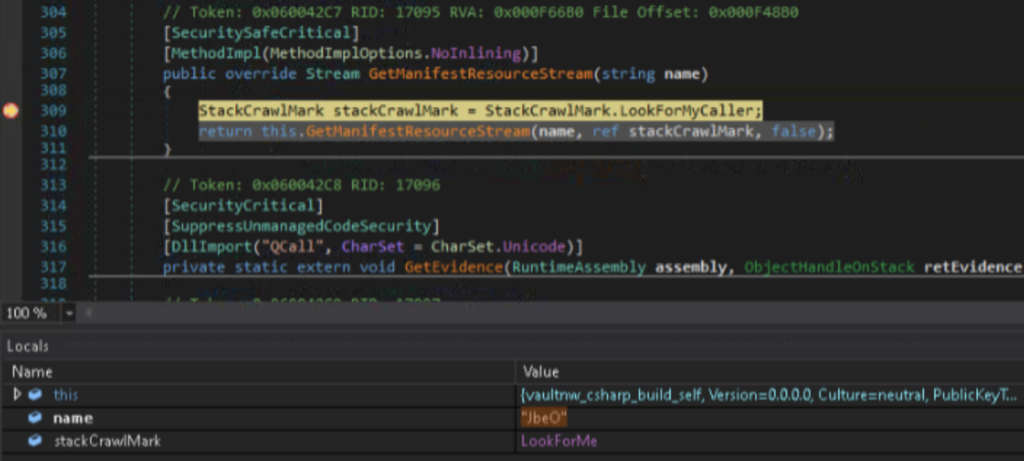

The GetManifestResourceStream method is used to access embedded resources at runtime, so to test our hypothesis, let’s set a breakpoint on it and run the sample under debugging.

As we expected, the breakpoint triggered. Now, following the call chain a little further, we can see how the read resource is passed into a method with token 0x0600018C for decryption. Let’s examine this method more closely in the cleaned version.

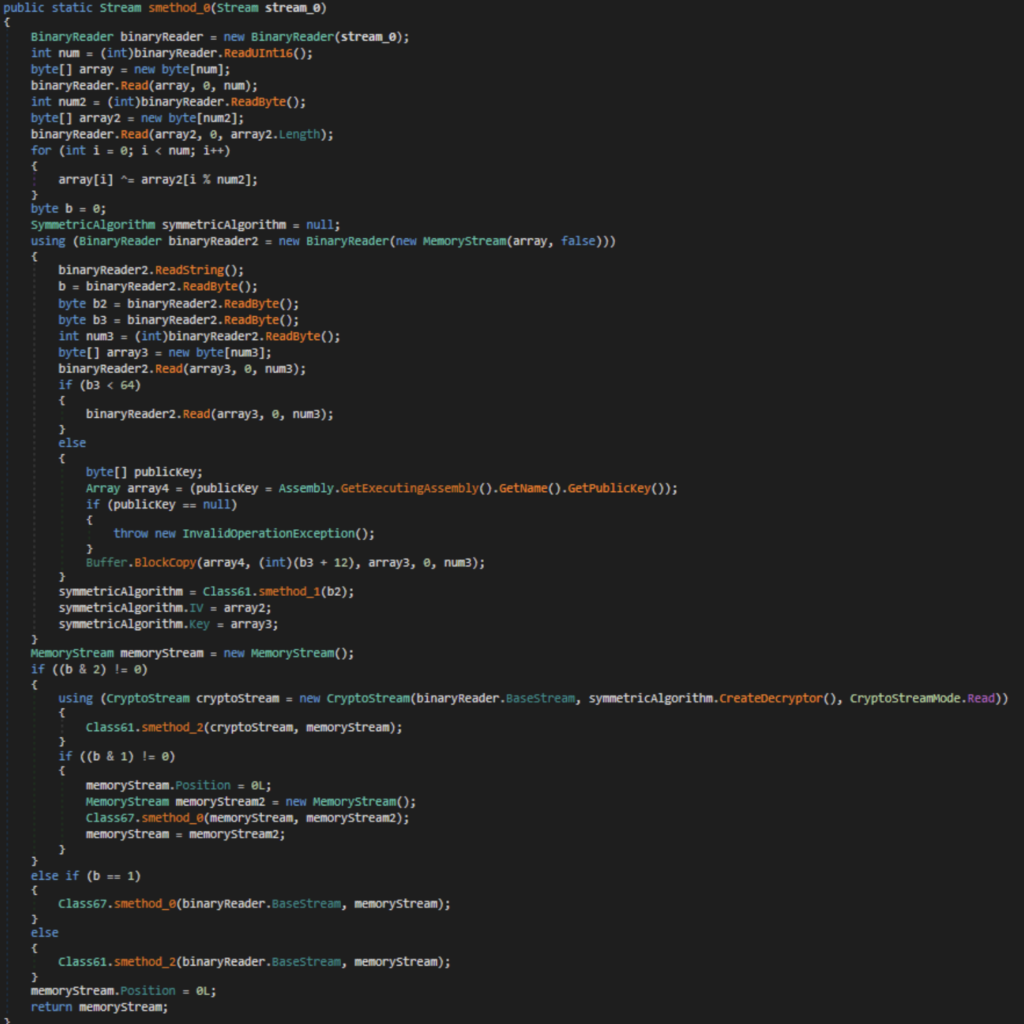

Initially, two arrays are read in the following format: size and data. Subsequently, the first array is decrypted using an XOR operation, with the second array functioning as a key. After this, the first array acts as a header from which parameters for ensuing actions are read.

Now, let’s examine this structure with a HEX editor.

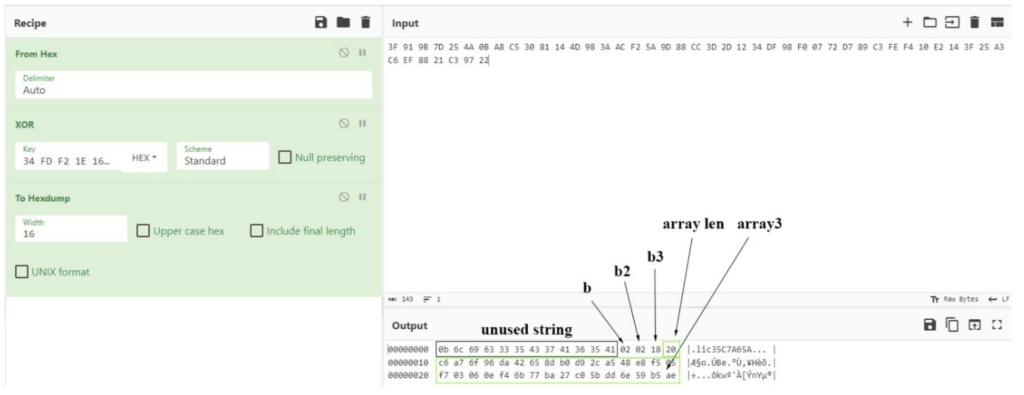

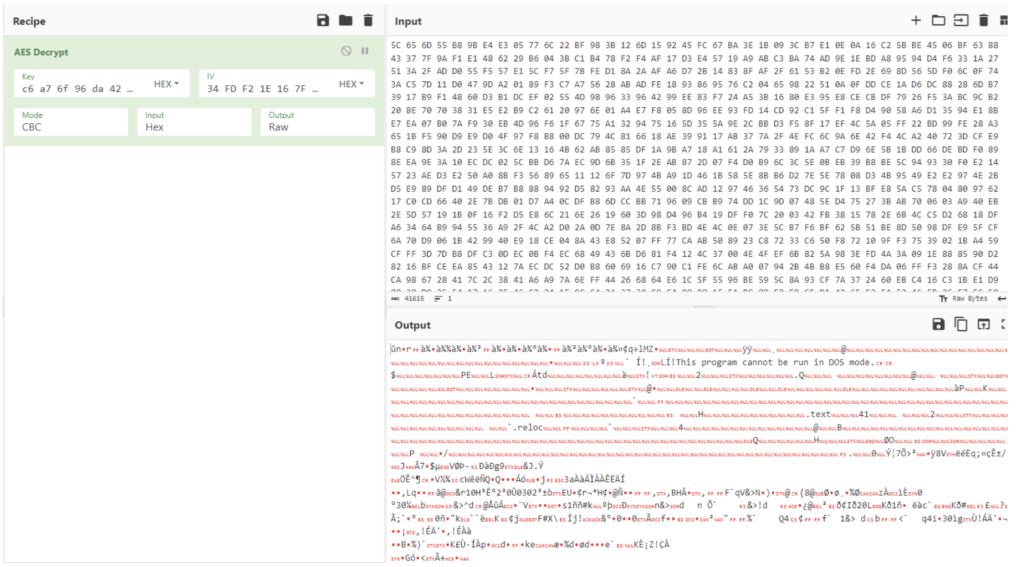

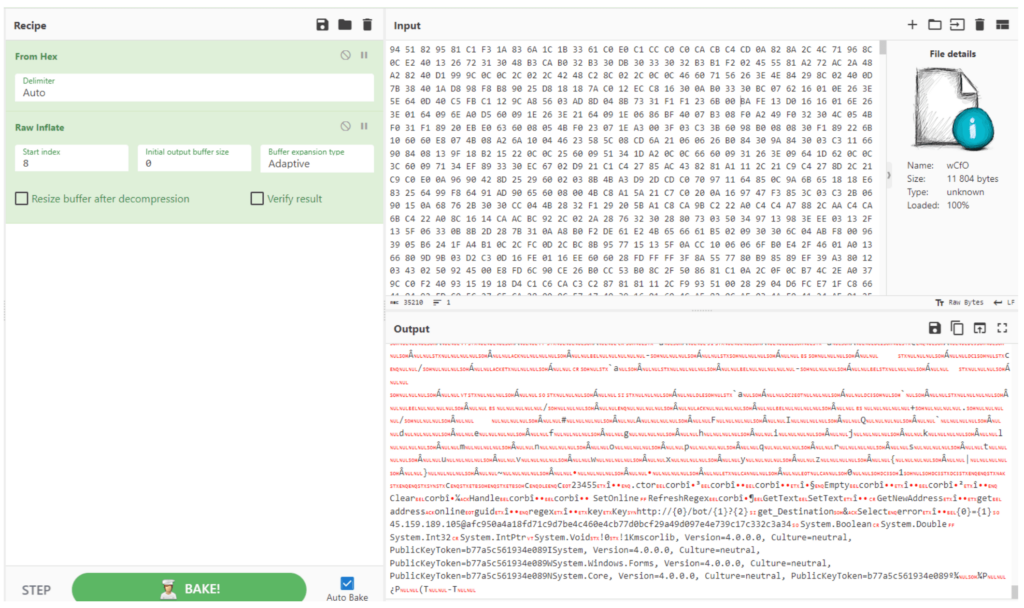

We can use CyberChef to extract the header for further analysis.

Now that we have access to the header, we can examine the variable values in the decryption method logic in more detail.

Variable b, at first glance, appears to be a bit field that can include the following values:

1 – Indicates whether the resource is compressed (spoiler)

2 – Indicates whether the resource is encrypted

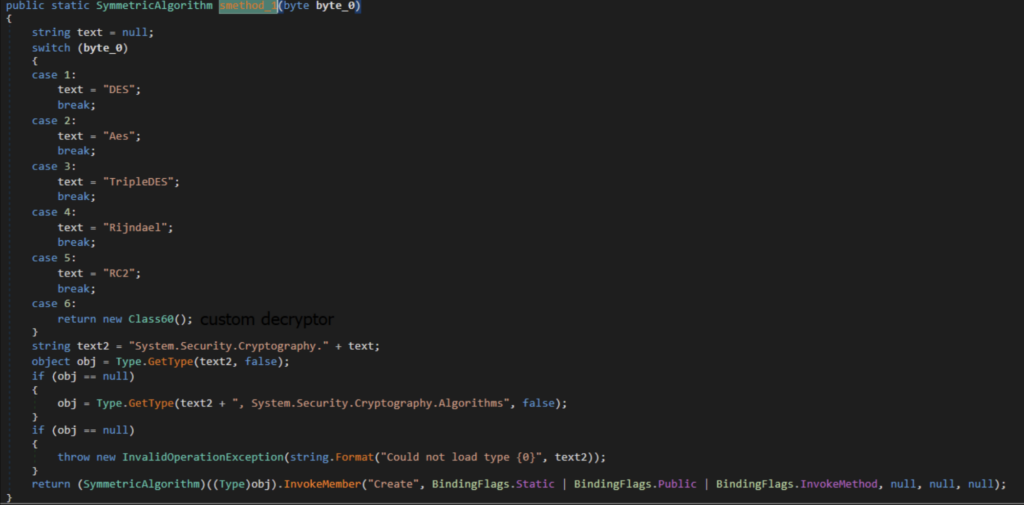

- Variable b2 defines the algorithm for decrypting the resource.

- Variable b3 is a dummy.

- Variable array3 is the key for decryption with the chosen algorithm.

As we can see, in our case the resource is only encrypted, and the decryption algorithm is AES.

It’s also important to note here that variable array2 is used, not only as an XOR key for the header, but also as an initialization vector for the decryption algorithm.

Now we have enough information to decrypt the resource ourselves.

After decryption, we’re met with “This program cannot be run in DOS mode”. Let’s feed the resulting executable file into DIE to confirm it’s a .NET assembly. So, we load it into dnSpy.

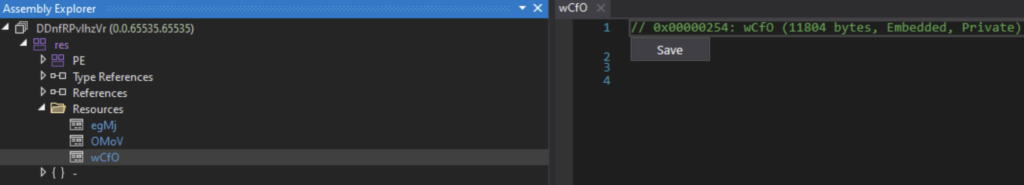

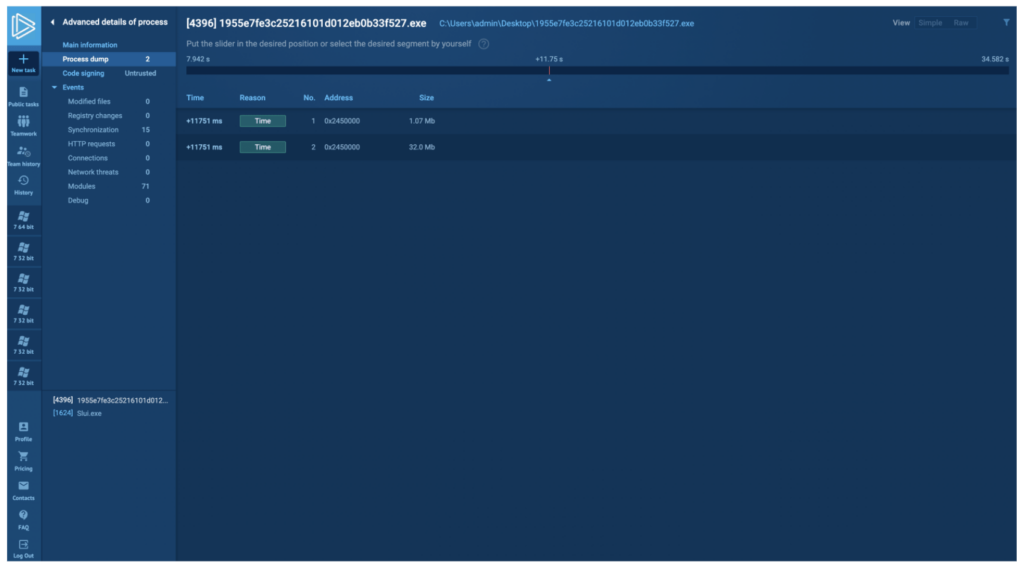

Inside, we find three additional resources, but no further code. The file we’ve obtained is merely a vessel for other resources. However, we remain undeterred and press on with our analysis. We’ll focus on unpacking the most sizable resource named “wCfO” (since the other two resources only vary slightly, we’ll omit them from this analysis).

Approaching the Finish Line of LaplasClipper analysis

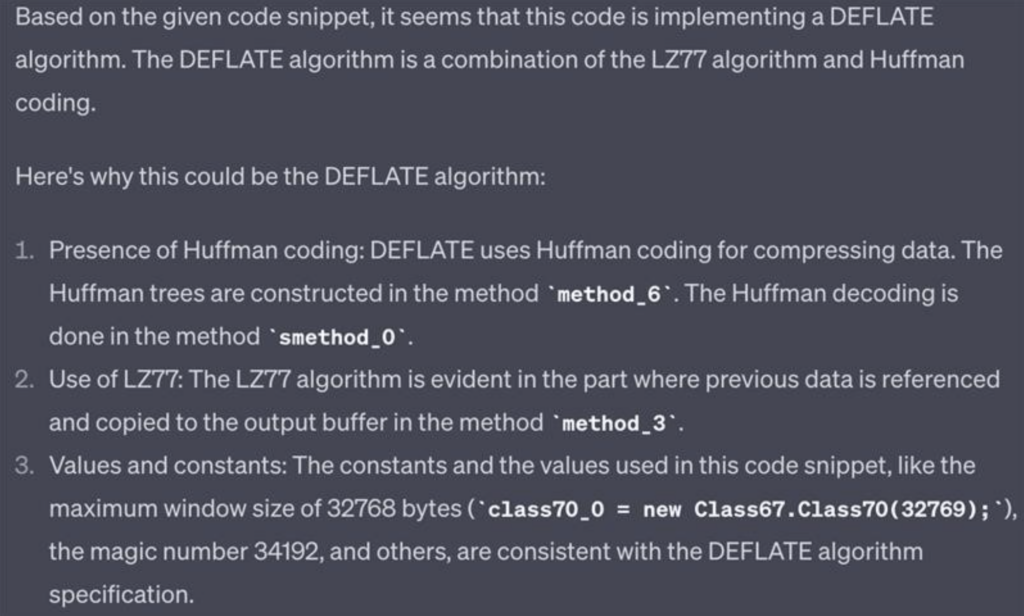

When we replicate the previous steps with the “wCfO” resource, we find that the variable b equals one. From the resource decryption method code, we deduce that if b equals one, control shifts to the Class67.smethod_0 method. When our manual examination of this routine failed to provide results, we decided to enlist the help of a cyber-assistant in the form of GPT-4. We fed it an approximately 500-line snippet, and the output was unexpected.

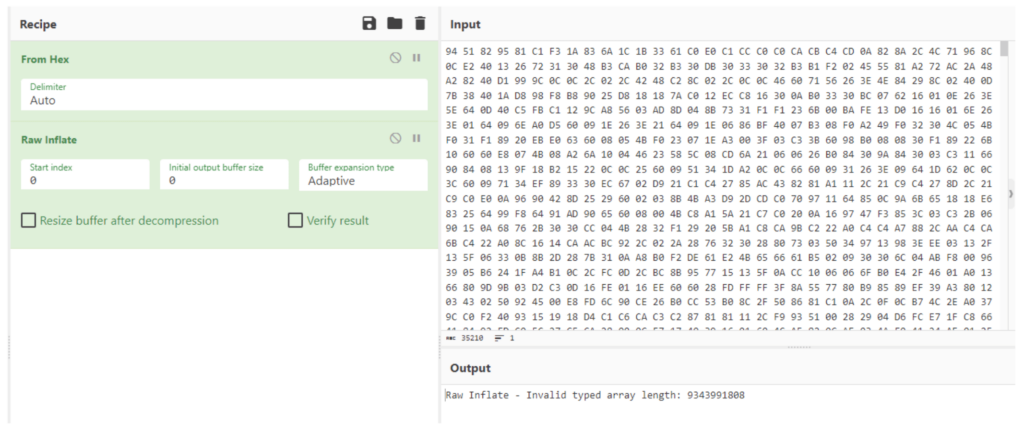

To our relief, GPT managed to extract the compression algorithm from the clutter. What remains is a relatively minor task: employing CyberChef one more time (remembering to remove the header from the resource before decompression).

However, we encountered a hurdle here too. The error could be due to meta-information at the start of the resource or a modified compression algorithm. Nevertheless, we determined an offset empirically, which allows us to unlock the internal information of our resource.

Congratulations! We’ve successfully reached the heart of our test subject. The C2 server address and the key are now clearly in view.

By the way, if you want to analyze the process dump yourself, you can easily download it from this task in ANY.RUN.

For further functioning, the sample uses a C2 address and a key to communicate with API endpoints over HTTP/S protocol (T1071.001):

- /bot/get – Query C2 for a visually similar wallet address for further substitution

- /bot/regex – Obtain regex expression from C2 to replace only matching wallet addresses

- /bot/online – Inform C2 that the victim is active

Wrapping up

In this article, we’ve dissected a fresh malware sample from the LaplasClipper family, developed on the .NET platform and obfuscated using Babel.

In the process of our research, we’ve uncovered the sample’s internal settings, examined some techniques leveraged by the obfuscator to complicate the sample analysis, and outlined strategies to counter them.

Our findings provide a solid understanding of the fundamental principles of protective mechanisms on the .NET platform. It’s critical to recognize that even the most complex protective methods rest on basic concepts, which are essential to understand and identify.

Want more malware analysis content? Learn more about common obfuscation methods and how to defeat them in our recent GuLoader analysis. Or read about the encryption and decryption algorithms of PrivateLoader.

Lastly, a few words about us before we wrap up. ANY.RUN is a cloud malware sandbox that handles the heavy lifting of malware analysis for SOC and DFIR teams. Every day, 300,000 professionals use our platform to investigate incidents and streamline threat analysis.

Request a demo today and enjoy 14 days of free access to our enterprise plan.

Collected IOCs

Analyzed file:

| MD5 | 1955e7fe3c25216101d012eb0b33f527 |

|---|---|

| SHA1 | f8a184b3b5a5cfa0f3c7d46e519fee24fd91d5c7 |

| SHA256 | 55194a6530652599dfc4af96f87f39575ddd9f7f30c912cd59240dd26373940b |

Connections:

| Connections (IP) |

|---|

| 45[.]159.189.105 |

URIs:

MITRE ATT&CK Matrix

| Tactics | Techniques | Description |

|---|---|---|

| TA0005: Defense Evasion | T1027.002 – Obfuscated Files or Information: Software Packing | Attempts were made to make an executable difficult to analyze by encrypting and embedding the main logical part into resources section |

| T1622 - Debugger Evasion | Anti-debugging techniques are used | |

| TA0011: Command and Control | T1071.001 - Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols | Target utilizes HTTP/S protocol to communicate with C2 |

| TA0009: Collection | T1115 - Clipboard Data | Target accesses and modifies clipboard buffer |

| TA0007: Discovery | T1082 - System Information Discovery | Target accesses system specific information |

0 comments