The majority of malware on Windows OS is compiled executable files. And their popularity has led to a blockage at the delivery stage to the user. Fortunately, antivirus software on users’ PCs is good at detecting and blocking the malicious payload contained in these files.

But malware developers use various tricks to overcome this issue: hackers develop a program using other (less popular) file formats. One of them is JAR.

In this article, we will talk about one of the Java malware representatives – STRRAT. Follow along with our detailed behavior analysis, configuration extraction from the memory dump, and other information about a JAR sample.

What is a malicious Java archive?

A JAR file, a Java archive, is a ZIP package with a program written in Java. If you have a Java Runtime Environment (JRE) on your computer, the .jar file starts as a regular program. But some antivirus software may miss such malware, as it is not a popular format, but it can be easily analyzed in an online malware sandbox.

Let’s look at STRRAT, a trojan-RAT written in Java. Here are typical STRRAT tasks:

- data theft

- backdoor creation

- collecting credentials from browsers and email clients

- keylogging

The initial vector of STRRAT infection is usually a malicious attachment disguised as a document or payment receipt. If the victim’s device has already had JRE installed, the file is launched as an application.

How to analyze STRRAT’s Java archive

STRRAT usually has the following execution stages:

- The icacls launch to grant permissions

- Running a malware copy in the C:\Users\admin folder

- Persistence via schtasks

- Running a malware copy in the C:\Users\admin\AppData\Roaming folder

- Collecting and sending data to the server specified in the program

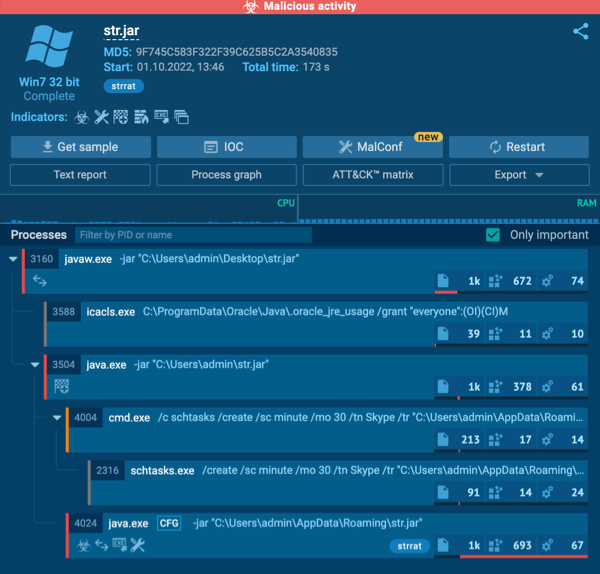

You can monitor this pattern of malware behavior in the STRRAT sample:

A JAR file replication

Replication is the first thing that catches your eye. We run the object from the desktop, then STRRAT creates a copy of the file: first in the C:\Users\admin folder and then in C:\Users\admin\AppData\Roaming. After that, they run consistently.

A Java file gets file access

The next step is that the malware uses icacls to control file access. The command grants all users access to the .oracle_jre_usage folder:

| icacls C:\ProgramData\Oracle\Java\.oracle_jre_usage /grant “everyone”:(OI)(CI)M |

Application launch of STRRAT malware

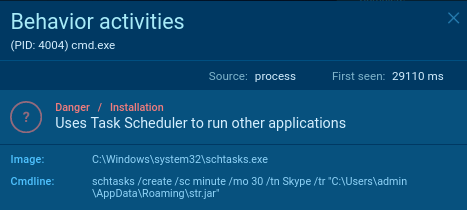

Then malware creates a task in the Scheduler using the command line:

| schtasks /create /sc minute /mo 30 /tn Skype /tr “C:\Users\admin\AppData\Roaming\str.jar |

The task is to use the Task Scheduler to run malware on behalf of the legal Skype program every 30 minutes.

Now let’s see the details of the 3504 process:

- Malware changes the autorun value

- it writes malware into the startup menu

So we can expect STRRAT to launch again after the OS reboot.

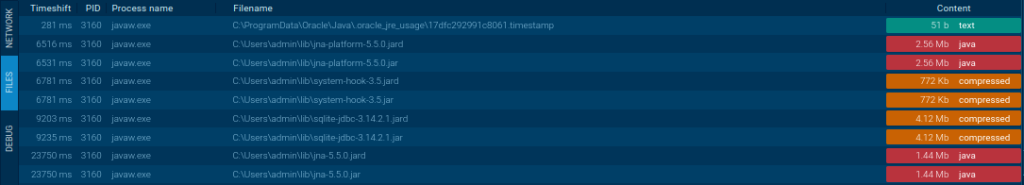

File creation of JAR malware

STRRAT’s process creates additional JAR files downloaded from public repositories.

The trojan downloaded and then created the library files from the Internet. If you run the malware through CMD, you can see them yourself. And this scenario is quite unusual – we can find the program execution logs if malware is run with CMD.

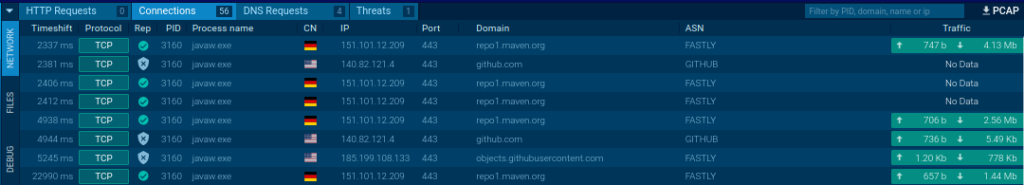

STRRAT network traffic analysis

ANY.RUN online malware sandbox provides detailed information about Network traffic in the Connections tab.

Go to the files tab to see that the library files are loading, which is necessary for further malware execution.

STRRAT downloads the following JAR libraries:

- jne

- sqllite

- system-hook

Besides data transferring, we can notice the constant attempts to connect with the 91[.]193[.]75[.]134 IP address.

Malicious Java archive’s IOCs

The significant part of the analysis is that you can get IOCs very fast.

How to extract STRRAT malware configuration

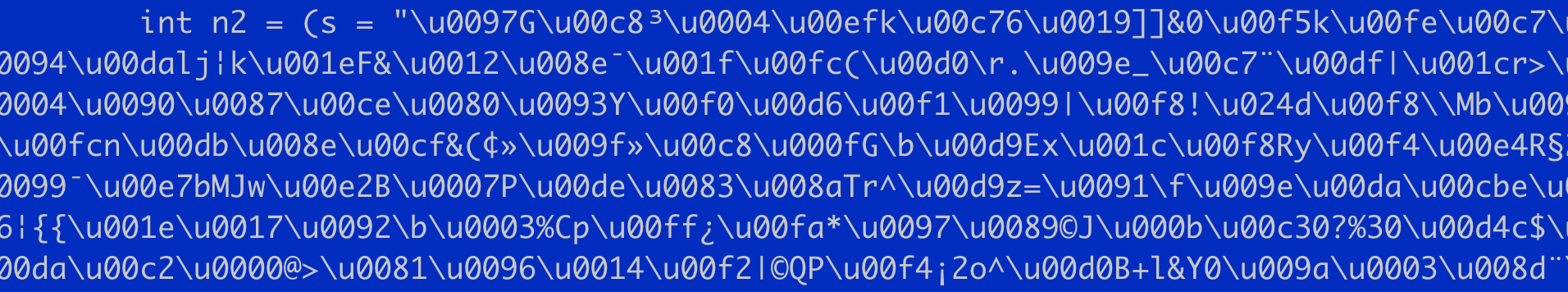

To retrieve the malware configuration, we use PH and find all lines. Then filter them by the address we already know in Connections.

As a result, we find only one interesting string.

Brief string analysis shows that it contains separators in the form of “vertical dashes,” different configuration parameters:

- address

- port

- URL link

Additional options include:

- 2 places where malware needs to install itself (Registry and StartconfigurationSkype task

- proxy

- LID (license)

These data are included in the configuration we are looking for.

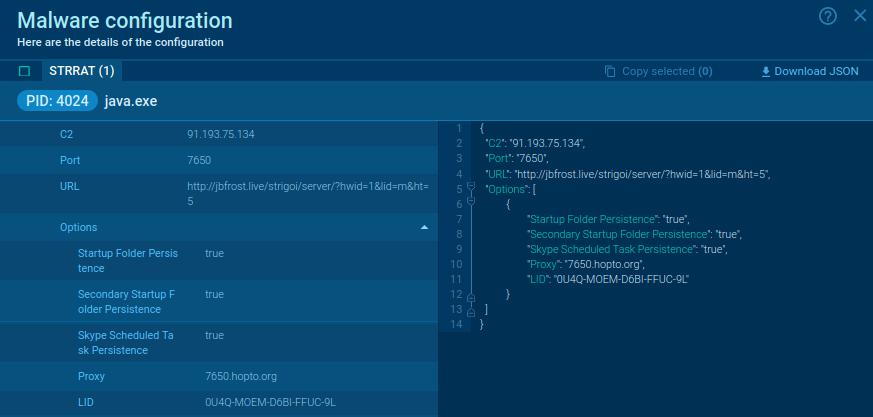

The line of interest is located in the heap area of memory. Let’s extract a dump of it and write a simple Python extractor. Try to extract it by yourself with the STRRAT malware configuration script that we have shared with you. If you use the code, this is the output data you should get:

And ANY.RUN’s version is already done for you. There is also a much faster way to get the data you need – review malware configurations right in our service, which will unpack the sample from memory dumps and extract C2s for you:

To sum it up

We have carried out the analysis of the malware written in JAVA and triaged its behavior in ANY.RUN online malware sandbox. We have written a simple extractor and derived the data. Copy the script of STRRAT and try to extract C2 servers by yourselves and let us know about your results!

ANY.RUN has already done this part for you, and the malware is detected automatically: it extracts the dump, pulls the configuration data, and presents results in an easy-to-read form.

STRRAT, Raccoon Stealer, what’s next? Please write in the comments below what other malware analysis you are interested in. We will be glad to add it to the series!

Check out other malware samples:

https://app.any.run/tasks/22ca1640-fcd8-4411-9757-8349af4d163f

https://app.any.run/tasks/56076b18-886b-46ca-aadb-e1d7d5de62cd

https://app.any.run/tasks/25cb57c8-a018-4ec1-bb98-74e5fe30e504

https://app.any.run/tasks/4ed8f7b5-e173-4011-b7fd-08f1bdbf40e

3 comments

You can easily decompile a jar file. I don’t know why you make it seem like you had to write code to get info when you can use bytecode viewer to literally read the code.

Thank you for the comment. But even if we decompile the JAR file, as you suggested, we won’t be able to see the data we get thanks to the script we have written. This is due to the fact that the malware code has been “twisted” by the obfuscator. And there is no clean IP, port or other data specified.

Working with malware memory dump, we can get already decrypted information without thinking how much and how obfuscated STRRAT code is.

Here is an example from the decompilation, where you can see that “nothing is visible” and is incomprehensible.

What do you think?