ANY.RUN’s team conducted an extensive malware analysis of CastleLoader, the first link in the chain of attacks impacting various industries, including government agencies and critical infrastructures.

It’s a unique walkthrough of its entire execution path, from a packaged installer to C2 server connection, as well as an overview of a parser developed to extract initialized local variables and automatically decode indicators of compromise (IOCs) featured in them.

Key Takeways

- CastleLoader is a stealthy malware loader used as the first stage in attacks against government entities and multiple industries.

- It relies on a multi-stage execution chain (Inno Setup → AutoIt → process hollowing) to evade detection.

- The final malicious payload only manifests in memory after the controlled process has been altered, making traditional static detection ineffective.

- CastleLoader delivers information stealers and RATs, enabling credential theft and persistent access.

- A full-cycle analysis allowed us to extract runtime configuration, C2 infrastructure, and high-confidence IOCs.

CastleLoader as an Initial Access Threat

CastleLoader is a malicious loader malware built to deliver and install other malicious components. It lays the groundwork for the attack, becoming its starting point.

This loader has commonly occurred in cyber attacks since early 2025. It gained popularity due to its high infection rate and universal nature, making it a powerful yet evasive tool.

In several observed campaigns, CastleLoader is delivered through the ClickFix social-engineering technique, where victims are tricked into manually executing malicious commands via fake verification or update prompts. In these cases, ClickFix acts as the initial access vector, while CastleLoader serves as the second-stage loader that deploys follow-on payloads directly in memory, helping attackers evade traditional file-based detection.

One of CastleLoader’s malicious campaigns is known to impact a total of 469 devices. It became a significant threat to organizations, especially US-based government entities. Its broader scope includes industries like IT, logistics, travel, and critical infrastructures across Europe.

CastleLoader is dangerous as a link in the chain delivering information stealers and RATs, making credential theft and persistent network access a high risk.

The loader’s popularity has inspired ANY.RUN’s malware analysis team to break down its malicious sample in order to uncover what it’s made of, retrieve signatures, and retrieve malware configurations.

Detect CastleLoader and More with Threat Intelligence Feeds

Modern malware like CastleLoader is designed to evade traditional detection. To keep up with the pace of adversaries, security teams need threat intelligence that reflects what attackers are using right now.

ANY.RUN’s Threat Intelligence Feeds provide real-time indicators extracted from live malware executions performed by thousands of SOC teams worldwide. With TI Feeds, they achieve:

- Faster threat detection: Identify active loaders, stealers, and RATs as soon as they appear in real-world attacks thanks to 99% unique data extracted from the latest sandbox analyses by 15K SOCs and 500K analysts.

- Higher confidence decisions: Indicators are backed by execution context, not guesswork or outdated reports.

- Improved SOC efficiency: Fewer false positives mean less alert fatigue and better use of analyst time.

- Stronger risk management: Early visibility into emerging malware families helps prevent business disruption.

By combining real-time sandbox intelligence with immediate IOC delivery, ANY.RUN’s TI Feeds help organizations stay ahead of fast-evolving threats like CastleLoader.

Initial Analysis: Sandbox Telemetry

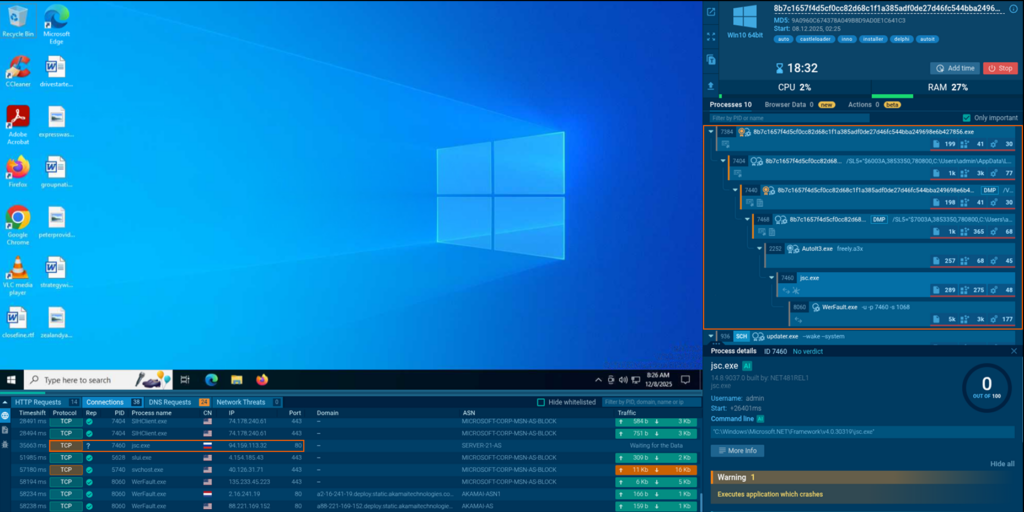

The analysis started with ANY.RUN’s Interactive Sandbox detonation.

What instantly grabs our attention here is a system process chain, at the end of which a request to 94[.]159[.]113[.]32:80 was sent. To understand this activity better, we switched to the binary analysis.

Static analysis: Inspecting Inno Setup Installer

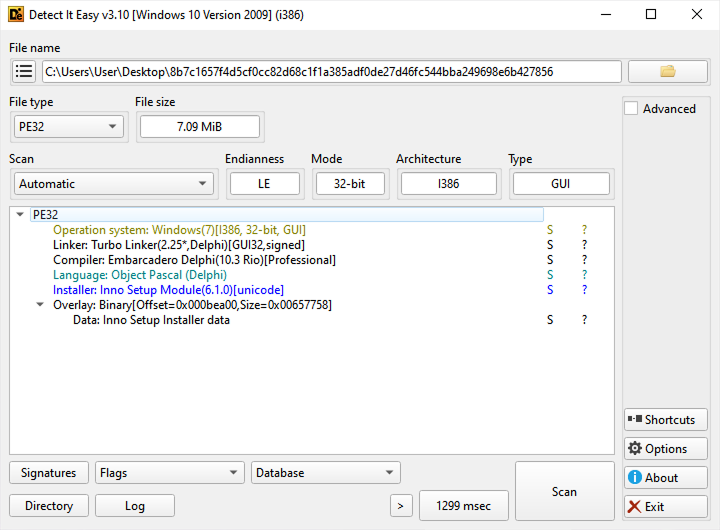

To get a basic overview of the binary, let’s process it via DIE (Detect It Easy).

It reveals that the binary consists of Object Pascal (Delphi) and Inno Setup Module (installer).

The next stage of the analysis requires the use of innoextract, a tool to unpack installers. We used a fork that allows you to unpack password-protected archives, which came in handy.

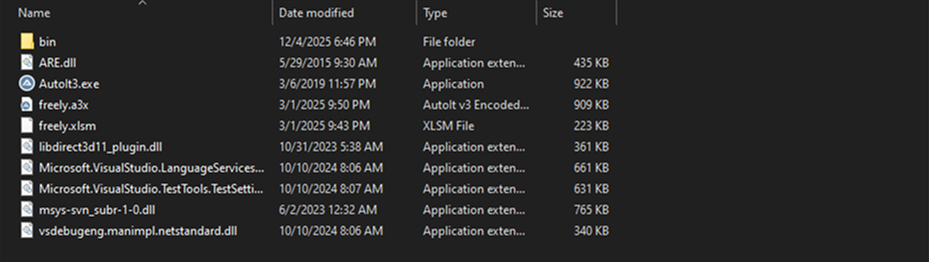

Archive extraction reveals several executables. At this point, it’s Autolt3.exe and the compiled script freely.a3x that grab our attention most. These are the files that directly participate in the calling chain. Other files, as it turned out later, aren’t related to the malware execution, and their role is unclear.

Next, let’s use Autolt-Ripper to extract compiled Autolt scripts from A3X containers. As a result of this, we get a file script.au3 containing 24,402 code lines. The majority of this code, which is responsible for the malicious chain, is unreadable:

Still, we are able to learn about the loaded modules and WinAPI wrappers:

// Some of the kernel32.dll module’s wrappers

Func _WINAPI_ASSIGNPROCESSTOJOBOBJECT ( $HJOB , $HPROCESS )

Local $ACALL = DllCall ( "kernel32.dll" , "bool" , "AssignProcessToJobObject" , "handle" , $HJOB , "handle" , $HPROCESS )

If @error Then Return SetError ( @error , @extended , False )

Return $ACALL [ 0 ]

EndFunc

Func _WINAPI_ATTACHCONSOLE ( $IPID = + 4294967295 )

Local $ACALL = DllCall ( "kernel32.dll" , "bool" , "AttachConsole" , "dword" , $IPID )

If @error Then Return SetError ( @error , @extended , False )

Return $ACALL [ 0 ]

EndFunc

Func _WINAPI_ATTACHTHREADINPUT ( $IATTACH , $IATTACHTO , $BATTACH )

Local $ACALL = DllCall ( "user32.dll" , "bool" , "AttachThreadInput" , "dword" , $IATTACH , "dword" , $IATTACHTO , "bool" , $BATTACH )

If @error Then Return SetError ( @error , @extended , False )

Return $ACALL [ 0 ]

EndFunc

Func _WINAPI_CREATEEVENT ( $TATTRIBUTES = 0 , $BMANUALRESET = True , $BINITIALSTATE = True , $SNAME = "" )

If $SNAME = "" Then $SNAME = Null

Local $ACALL = DllCall ( "kernel32.dll" , "handle" , "CreateEventW" , "struct*" , $TATTRIBUTES , "bool" , $BMANUALRESET , "bool" , $BINITIALSTATE , "wstr" , $SNAME )

If @error Then Return SetError ( @error , @extended , 0 )

Local $ILASTERROR = _WINAPI_GETLASTERROR ( )

If $ILASTERROR Then Return SetExtended ( $ILASTERROR , 0 )

Return $ACALL [ 0 ]

EndFunc

Func _WINAPI_CREATEJOBOBJECT ( $SNAME = "" , $TSECURITY = 0 )

If Not StringStripWS ( $SNAME , $STR_STRIPLEADING + $STR_STRIPTRAILING ) Then $SNAME = Null

Local $ACALL = DllCall ( "kernel32.dll" , "handle" , "CreateJobObjectW" , "struct*" , $TSECURITY , "wstr" , $SNAME )

If @error Then Return SetError ( @error , @extended , 0 )

Return $ACALL [ 0 ]

EndFunc

Func _WINAPI_CREATEMUTEX ( $SMUTEX , $BINITIAL = True , $TSECURITY = 0 )

Local $ACALL = DllCall ( "kernel32.dll" , "handle" , "CreateMutexW" , "struct*" , $TSECURITY , "bool" , $BINITIAL , "wstr" , $SMUTEX )

If @error Then Return SetError ( @error , @extended , 0 )

Return $ACALL [ 0 ]

EndFunc Several WinAPI wrappers may potentially participate in attacks for further system infection, because it’s the Autolt scrip that prepares the environment and control handover.

Key function calls

This combination of functions looks suspicious and hints at cross-process manipulations:

kernel32.GetProcAddress — Dynamic function resolution

kernel32.CreateFileW — Working with files

kernel32.CreateProcessW — Creating processes

kernel32.CreateMutextW — Creating mutexes

kernel32.OpenProcess — Opening process descriptors

kernerl32.ReadProcessMemory — Reading the memory of other processes

kernerl32.DuplicateTokenEx — Duplicating security tokens

kernelbased.AdjustTokenPriviliges — Manipulating the privileges

kernel32.WriteFile — Writing into filesSince full-scale deobfuscation would take up too much time, let’s switch to dynamic analysis for now.

Dynamic Analysis: Tracing Execution

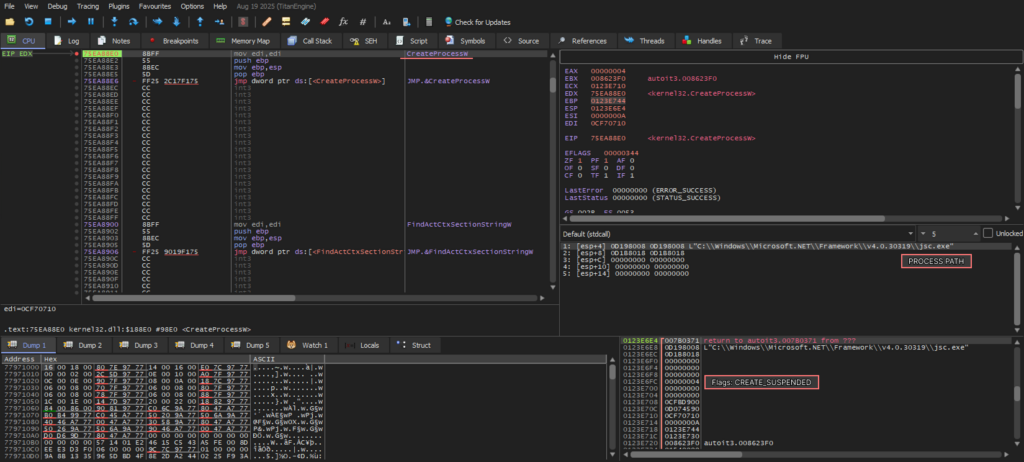

Let’s launch Autolt3.exe in x32dbg with breakpoints at functions that we’ve listed above, with the compiled script freely.a3x as a parameter.

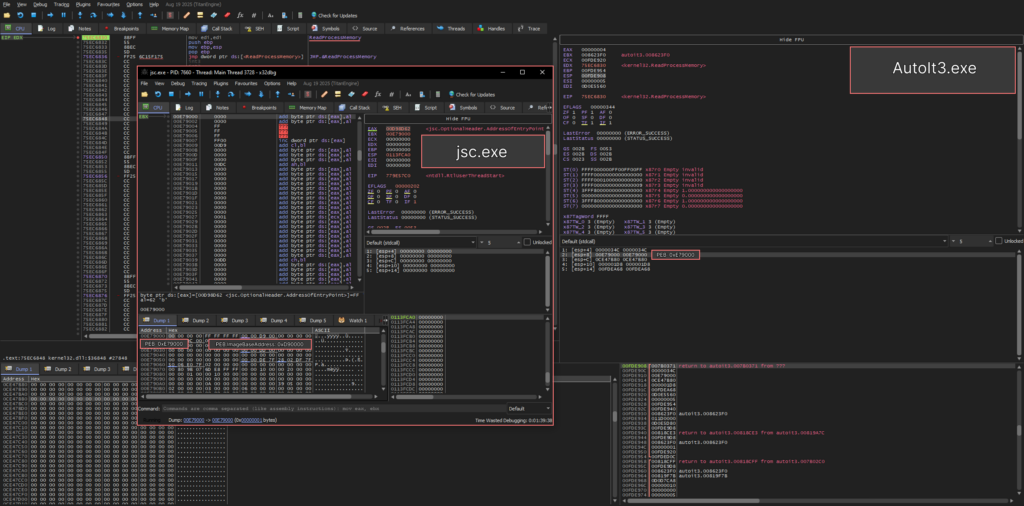

Soon after the initialization of Autolt3.exe, we see a kernel32.CreateProcessW call, where jsc.exe, the final link of our chain, is located.

Note: this is a JScript.NET compilator, a part of an older .NET Framework. What’s unusual is that no extra data is transmitted to lpCommanLine.

Also, there’s a CREATE_SUSPENDED flag in dwCreationFlags, which points to an uncommon use of jsc.exe. But how does it get the payload?

The next string of calls reveals this:

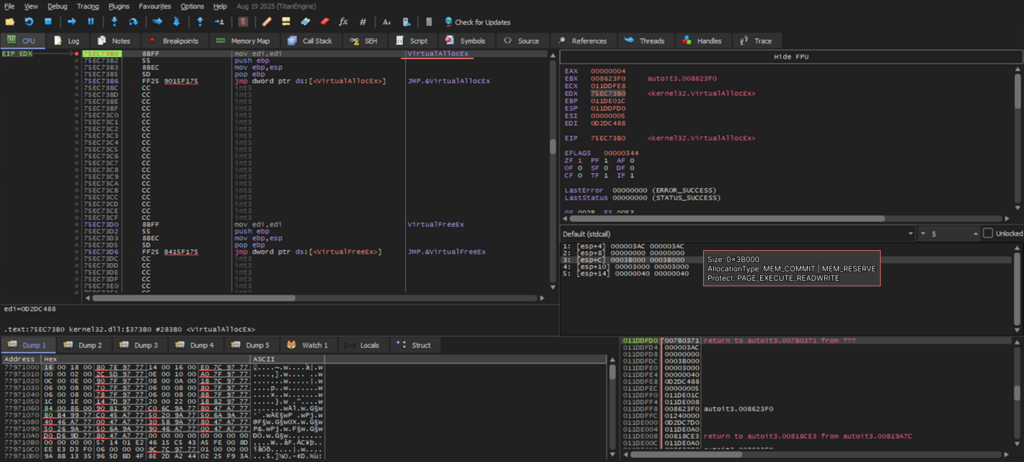

- kernel32.CreateProcessW creates the jsc.exe process flagged as CREATE_SUSPENDED.

- kernel32.GetThreadContext delivers registries — the context of the main flow. This is typical for the preparation to process hollowing.

- kernel32.VirtualAllocEX allocates a 0x3B000-sized memory area in jsc.exe process with MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE flags and PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE protection. This allows you to place and launch any code.

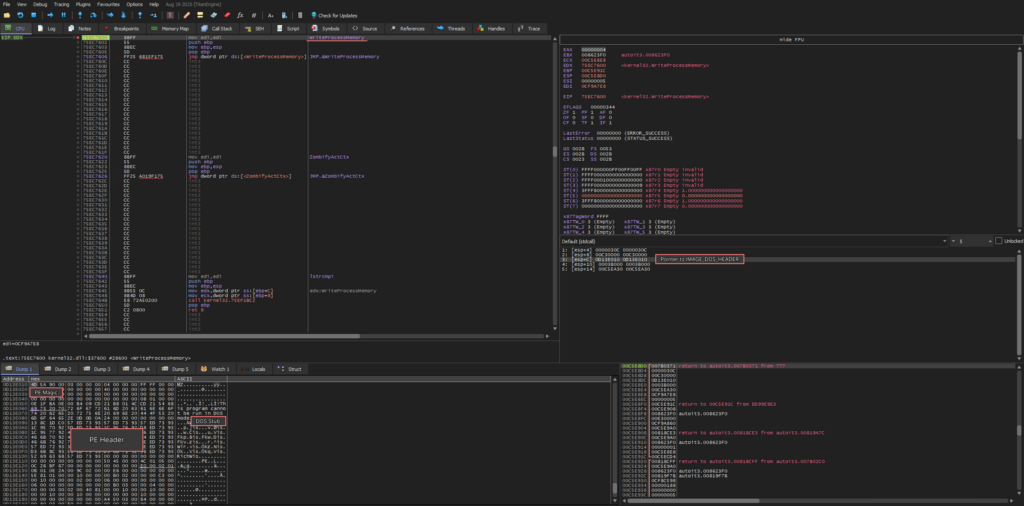

To confirm this and extract the key module, let’s keep tracing the malware. The next critical call is kernel32.WriteProcessMemory. Among its arguments is a pointer to a buffer with loaded data, featuring familiar PE Magic and DOS Stub signatures. This clearly means that a PE file is injected into the jsc.exe process.

At this stage, we can safely dump a clean binary from the memory.

The payload is revealed, but we continue unraveling the entire chain until the final call — kernel32.ResumeThreat. This will help us make sure that the malware doesn’t do anything extra, like embedding another hidden process, before the control handover.

The next critical step is the call of kernel32.ReadProcessMemory. At this stage, the threat obtains a pointer to the PEB (Process Environment Block) structure, from which it extracts a PEB.ImageBaseAddress (base load address). This address is further rewritten to the injected PE module. That’s crucial for standard loading mechanisms of Windows, including early ntdll.LdrInintializeThunk initialization, as this allows for the correct processing of import tables, relocating, and restoring of the image’s data.

After this, kernel32.WriteProcessMemory is called, which completes the stage of replacing the base address in the PEB structure.

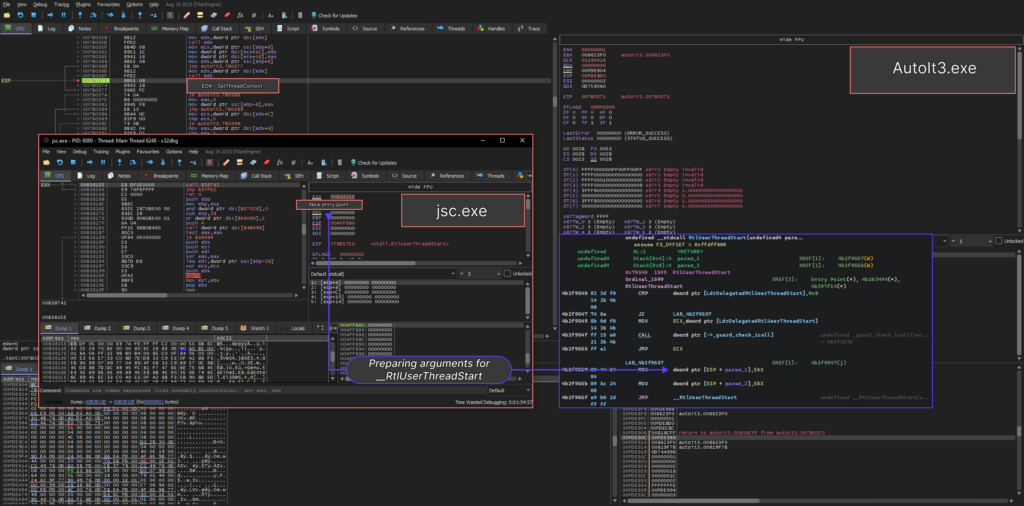

Next, kernel32.SetThreadContext is invoked, almost finalizing the process hollowing. At this stage, the malware writes a pointer to the entry point of the injected module into the EAX register.

After the call to kernel32.ResumeThread, control is handed over to ntdll.LdrInitializeThunk, which performs loader initialization and prepares the process execution environment.

Once initialization is complete, ntdll.LdrInitializeThunk calls ntdll.NtContinue, restoring the execution context.

As a result, the execution continues from the address stored in the EIP register. This is the beginning of the ntdll.RtlUserThreadStart procedure, which places the entry point from the EAX register onto the stack in accordance with the __stdcall calling convention and then hands over control to ntdll.__RtlUserThreadStart.

Notably, this is not a common process hollowing. The regular method includes the extraction of the original memory area via NtUnmapViewOfSection. But in CastleLoader’s case, the malware dismisses this step intentionally.

To monitoring tools like System Informed, the process doesn’t look off. It’s also not a part of an event chain known to EDR.

This decreases the probability of detection without disrupting the processing of all tables and structures, ensuring normal functioning of the injected module.

Preliminary Results

Inno Setup as a Delivery Container

The original Inno Setup installer turned out to be a container with a set of auxiliary files, among which the AutoIt3.exe + freely.a3x combination played a key role. We were able to extract and partially decompile the AutoIt script; however, most of its logic was heavily obfuscated and consisted of numerous wrappers around the WinAPI.

AutoIt Script and Process Hollowing via jsc.exe

Static analysis showed that the script prepares the environment and launches the next stage, while dynamic analysis confirmed that after jsc.exe is started, one of the process hollowing techniques is executed: another executable module is injected into the process’s address space.

As a result, we discovered a fully functional PE file — the main CastleLoader module — inside the process and successfully dumped it for further analysis.

Evasion Through Multi-Stage Execution

Such a sophisticated multi-stage execution chain was not implemented merely to complicate analysis, but specifically as an attempt to conceal the execution of the main payload from detection mechanisms. Using Inno Setup as a container, an AutoIt script as an intermediate layer, and process hollowing over jsc.exe, allows CastleLoader to distribute across several components that appearbenign at first glance.

Post-Execution Artifacts on Disk

After the loader completes its execution, the files extracted by the Inno Setup installer remain on the disk. This may either be a deliberate attempt to mimic the normal behavior of legitimate software, which often leaves installation artifacts behind, or simply an implementation flaw. Given the relative novelty of the malware family, it’s probably the latter.

Impact on Detection Mechanisms

Static signatures, simple behavioral heuristics, and process monitoring systems become ineffective

This execution model reduces the likelihood of detection, as each individual stage appears legitimate, and the final payload only manifests in memory after the controlled process has been altered. As a result, static signatures, simple behavioral heuristics, and process monitoring systems become ineffective. A fully functional malicious module exists only at runtime, and only within an already modified process. y manifests in memory after the controlled process has been altered. As a result, static signatures, simple behavioral heuristics, and process monitoring systems become ineffective. A fully functional malicious module exists only at runtime, and only within an already modified process.

Going Back to Static Analysis

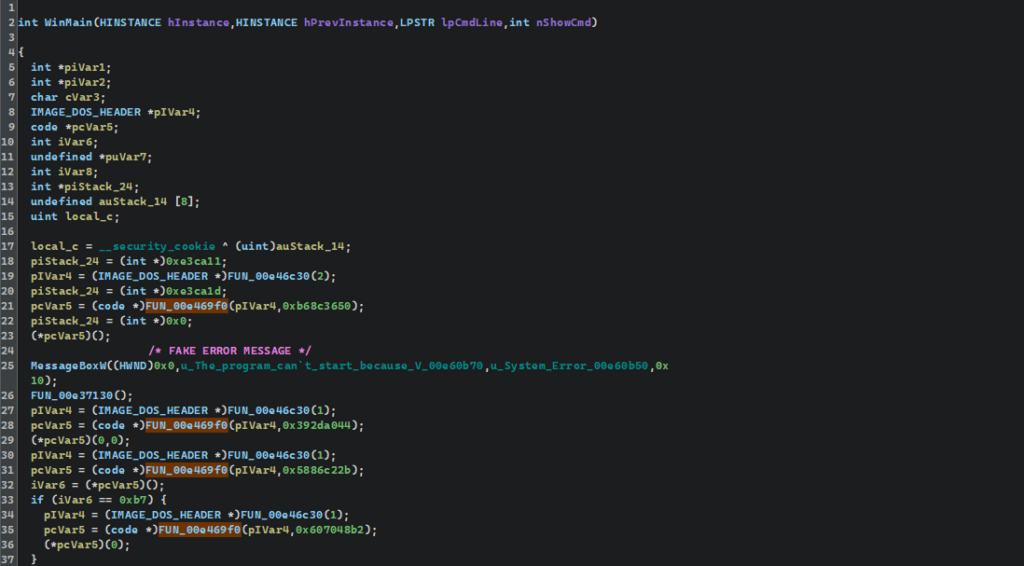

After uploading the memory dump to Ghidra, let’s start the analysis of its execution context. Right after opening the dump we see a kernel32.MessageBoxW call, which displays a fake error message: “System Error. The program can’t start because VCRUNTIME140.dll is missing from your computer. Try reinstalling the program to fix this problem.”

After that, the execution of malicious code continues.

During the analysis, we can see functions with unclear values. By studying their references, we see that they are actively called throughout the program’s execution.

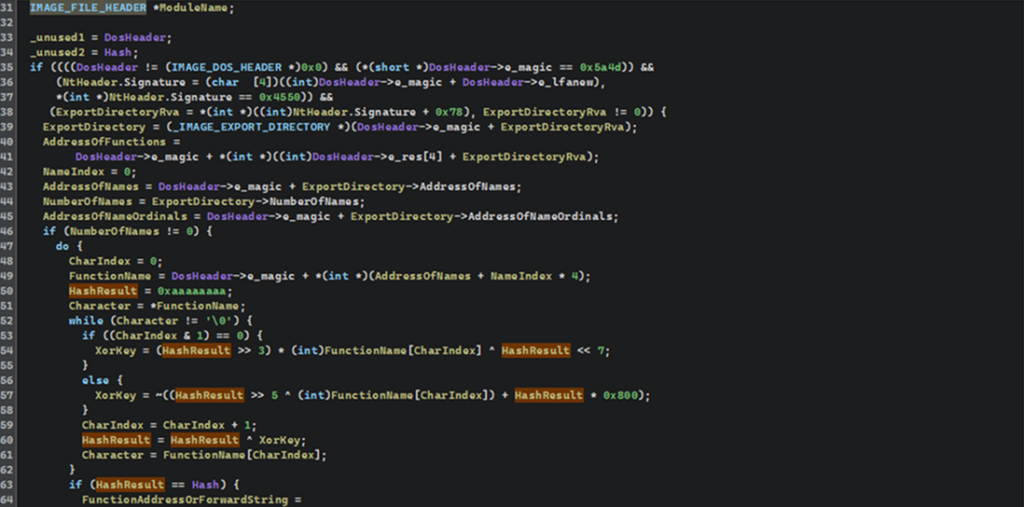

In FUN_00e469f0, the first argument of the function is a pointer to the start of the PE module. At first, the value is dereferenced and checked for a DOS heading 0x5A4D (“MZ”). This is followed by NT heading’s validation and decomposition of PE’s key structures.

The function manually gets access to the export table, allowing for a rewrite of the basic module address (IMAGE_DOC_HEADER*). Then each exported character goes through an embedded hash function, while the calculated hash is compared to the initial value.

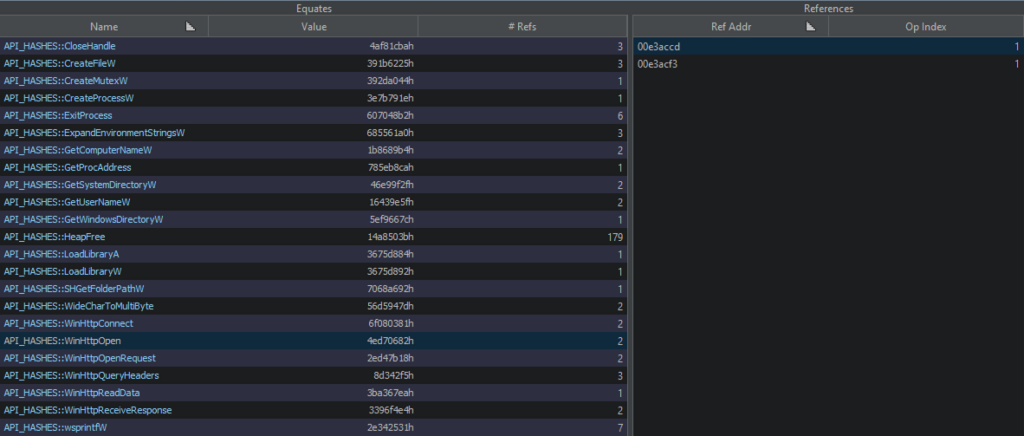

Since we now know the origin of each digest and the way the function resolves the required APIs by hash, we can gather a set of potentially used network functions, run them through the hashing algorithm, and generate an enumeration (enum) for Ghidra.

Using the script, we automatically replaced all hashes with their corresponding function names — the result can be seen in the Equates Table. Each hash is now tied with a readable API name, along with the number of cross-references to it.

This also makes it easy to track all calls of these functions via the References section, where for each usage point there’s a reference to the corresponding API address.

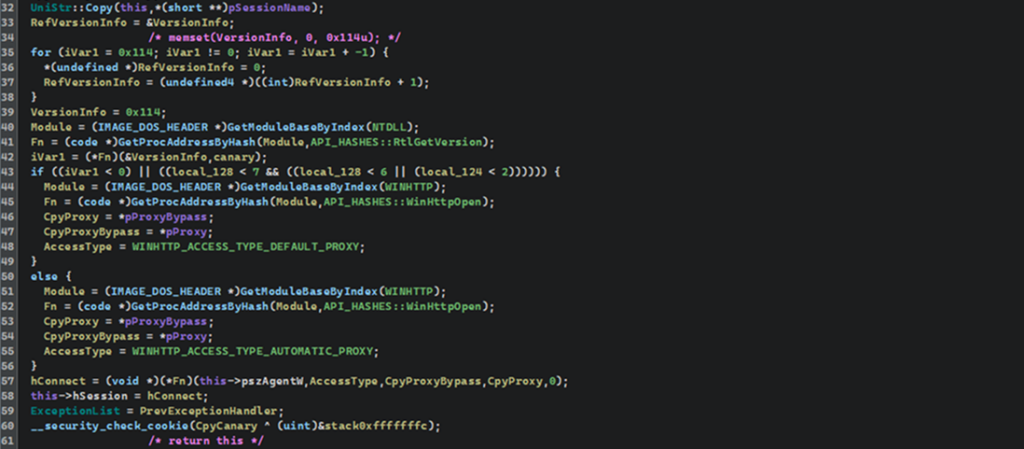

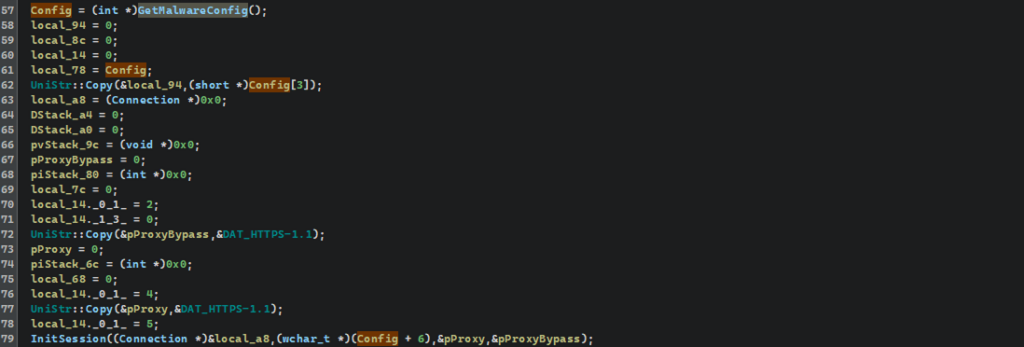

After generating the enum and substituting API names in the Equates Table, we see that the binary uses WINHTTP.WinHttpOpen. Cross-references to the corresponding hash prove that. We annotated a function with this call to make it easier to follow the logic. Then, by examining the cross-references to this function, we can move to its caller — the point where the HTTP session setup begins.

While examining the HTTP connection’s initialization stage, we identified a function that returns a pointer to the data structure used as the initial configuration for the network logic. The format of this structure isn’t clear; but the fact that it’s there suggests the presence of a dedicated procedure responsible for creating and populating the configuration structure.

We annotated several references around the returned pointer and proceeded to analyze the function that forms the configuration structure. This is done to restore its components and understand which parameters are used for network connection.

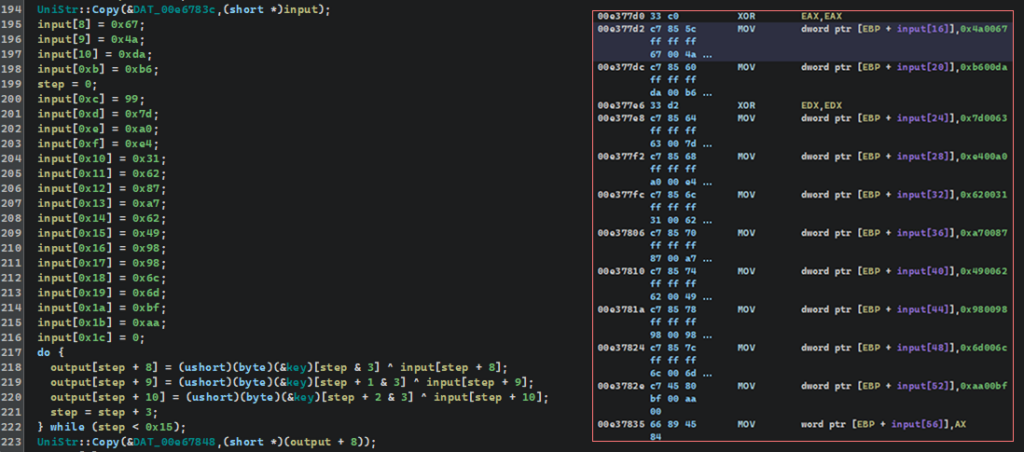

Several nested functions lead us to a large-scale procedure, during which the configuration data is prepared. Its values aren’t static strings, but a mass of encrypted bytes packaged into DWORDs with two UTF-16LE characters and placed right on the stack. This data is postprocessed with a simple bit-by-bit transformation into string buffers.

The temporary buffers are then passed to UniStr::Copy and pasted into fixed global addresses. All of these addresses are laid out sequentially in .data sections, effectively forming a single contiguous configuration block.

At the end, the function returns the address of the first element (0xE67830), allowing the entire data set to be used as an array or a structure with fixed offsets.

An example of a decryption algorithm

input[8] = 0x67;

input[9] = 0x4a;

input[10] = 0xda;

input[0xb] = 0xb6;

step = 0;

input[0xc] = 99;

input[0xd] = 0x7d;

input[0xe] = 0xa0;

input[0xf] = 0xe4;

input[0x10] = 0x31;

input[0x11] = 0x62;

input[0x12] = 0x87;

input[0x13] = 0xa7;

input[0x14] = 0x62;

input[0x15] = 0x49;

input[0x16] = 0x98;

input[0x17] = 0x98;

input[0x18] = 0x6c;

input[0x19] = 0x6d;

input[0x1a] = 0xbf;

input[0x1b] = 0xaa;

input[0x1c] = 0;

do {

output[step + 8] = (ushort)(byte)(&key)[step & 3] ^ input[step + 8];

output[step + 9] = (ushort)(byte)(&key)[step + 1 & 3] ^ input[step + 9];

output[step + 10] = (ushort)(byte)(&key)[step + 2 & 3] ^ input[step + 10];

step = step + 3;

} while (step < 0x15);

UniStr::Copy(&DAT_00e67848,(short *)(output + 8));

// In this fragment, there’s a small static block of data (byte array) formed.

// Then, bit-by-bit, it’s decrypted by undergoing XOR operation with a cyclic one-table key.

// Decrypted bytes are extended to UTF-16LE characters and written into an exit buffer, which is then pasted into the global memory region

// via UniStr::Copy.

// Basically, this is a simple custom decryption of strings using fixed bytes arrays and cyclic XOR masking by index with transformation to Unicode.Building a Custom Parser

After manually decrypting several strings, we realized that the process could be automated. The extraction logic used by CastleLoader is known: it has a single UTF-16LE DWORD pattern, loop construct, and fixed addresses, from which the XOR bytes are taken. That’s enough to identify the repeating code fragments and write a Python script that extracts all strings from the dump in a single pass.

Parser’s results

E32E6D: %s/settings/%s

E33F4C: windows_version

E3417F: machine_id

E33D70: access_key

E35E40: %s/tasks/complete/id/%lu

E37732: http://94[.]159[.]113[.]32/service (C2)

E377D2: gM7dczM61ejubNuJljRx (UserAgent)

E378A8: N3sBJNQKOyBSqzOgQSQVf9 (Mutex)

E3F4E9: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/133.0.0.0 Safari/537.36… and so on.

The analysis of the configuration function was the right call. We ended up with the entire strings array used by CastleLoader. As a result, we get the published script.

Most importantly, the resulting strings feature the very C2 address which we saw in the sandbox analysis. Now it’s extracted not as a secondary effect of network activity, but as a part of malware configuration. This decisively confirms its role and proves that retrieved IOCs are reliable for detection and analysis.

Final Observations

Since we wanted to demonstrate the entire analysis process from start to finish, we deliberately followed the extended analysis path, from coming up with hypotheses to testing and adjusting them. In practice, many of these stages could have been skipped.

ANY.RUN provides sufficiently detailed telemetry to significantly shorten the analysis.

ANY.RUN provides sufficiently detailed telemetry to significantly shorten the analysis. For example, we didn’t have to investigate the Inno Setup module, since the sample did not remove the extracted files afterwards.

The final process could have been dumped immediately, too, to bypass the intermediate stages, as it was the only one that actually interacted with the network and generated traffic.

Nevertheless, the full walkthrough proved valuable: it allowed us to reconstruct the entire execution chain, understand the loader’s internal logic, and verify that the extracted data really indicates CastleLoader’s presence. This approach gave us not only the final set of IOCs, but also an understanding of the mechanisms behind them.

About ANY.RUN

ANY.RUN is a leading provider of interactive malware analysis and threat intelligence solutions trusted by security teams worldwide. The platform combines real-time sandboxing with a comprehensive intelligence ecosystem, including Threat Intelligence Feeds, TI Lookup, and public malware submissions.

More than 500,000 security analysts and 15,000 organizations rely on ANY.RUN to accelerate investigations, validate TTPs, collect fresh IOCs, and track emerging threats through live, behavior-driven analysis.

By giving defenders an interactive, second-by-second view of malware execution, ANY.RUN enables faster detection, better-informed decisions, and a stronger overall security posture.

Discover how ANY.RUN can enhance your SOC — start your 14-day trial today.

IOCs

Analyzed Files

| Name | MD5 | SHA1 | SHA256 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8b7c1657f4d5cf0cc82d68c1f1a385adf0de27d46fc544bba249698e6b427856.exe (Inno Setup Installer) | 9A0960C674378A049B8D9AD0E1C641C3 | 0580A364AB986B051398A78D089300CF73481E70 | 8B7C1657F4D5CF0CC82D68C1F1A385ADF0DE27D46FC544BBA249698E6B427856 |

| freely.a3x (AutoIt Script) | AFBABA49796528C053938E0397F238FF | DD029CD4711C773F87377D45A005C8D9785281A3 | FDDC186F3E5E14B2B8E68DDBD18B2BDA41D38A70417A38E67281EB7995E24BAC |

| payload.exe (CastleLoader Core Module) | 1E0F94E8EC83C1879CCD25FEC59098F1 | 9E11E8866F40E5E9C20B1F012D0B68E0D56E85B3 | DFAF277D54C1B1CF5A3AF80783ED878CAC152FF2C52DBF17FB05A7795FE29E79 |

Network Indicators

C2 Server

- 94[.]159[.]113[.]32

HTTP Request

- http://94[.]159[.]113[.]32/service

Mutex

- N3sBJNQKOyBSqzOgQSQVf9

User-Agents

- gM7dczM61ejubNuJljRx

- Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/133.0.0.0 Safari/537.36

YARA Rules

rule CastleLoader {

meta:

author = "ANY.RUN"

date = "2025-12-02"

description = "Identifies CastleLoader malware samples"

threat = "CastleLoader"

strings:

$p1 = { 44 a0 2d 39 } //CreateMutexW

$p2 = { 82 06 d7 4e } //WinHttpOpen

$p3 = { 81 03 08 6f } //WinHttpConnect

$p4 = { 18 7b d4 2e } //WinHttpOpenRequest

$p5 = { e4 f4 96 33 } //WinHttpReceiveResponse

$p6 = { d8 da 54 96 } //ShellExecuteW

$p7 = { 5f 9e 43 16 } //GetUserNameW

$p8 = { b4 89 86 1b } //GetComputerNameW

condition:

all of ($p*)

}MITRE ATT&CK Techniques

| Tactic | Technique | Description |

|---|---|---|

| TA0002: Execution | T1059.010: AutoHotKey & AutoIT | Execution via AutoIt script (freely.a3x) |

| TA0005: Defense Evasion | T1027.002: Software Packing | Multi-stage: Inno Setup → AutoIt → PE injection |

| T1055.012: Process Hollowing | Process hollowing into jsc.exe | |

| T1106: Native API | API resolution via hash-based GetProcAddress | |

| T1140: Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information | Runtime XOR-decoding of configuration strings (C2, User-Agent, Mutex); obfuscated AutoIt script | |

| TA0007: Discovery | T1082: System Information Discovery | Collects computer_name, windows_version, machine_id |

| TA0011: Command and Control | T1071.001: Web Protocols | HTTP communication to 94[.]159[.]113[.]32:80/service |

nevergiveup-c

A reverse engineering and C/C++ development enthusiast with a focus on malware analysis, vulnerability research in binaries and systems, and the development of low-level libraries. Actively participates in CTF competitions and develops proof-of-concepts to study and explore advanced techniques.

0 comments